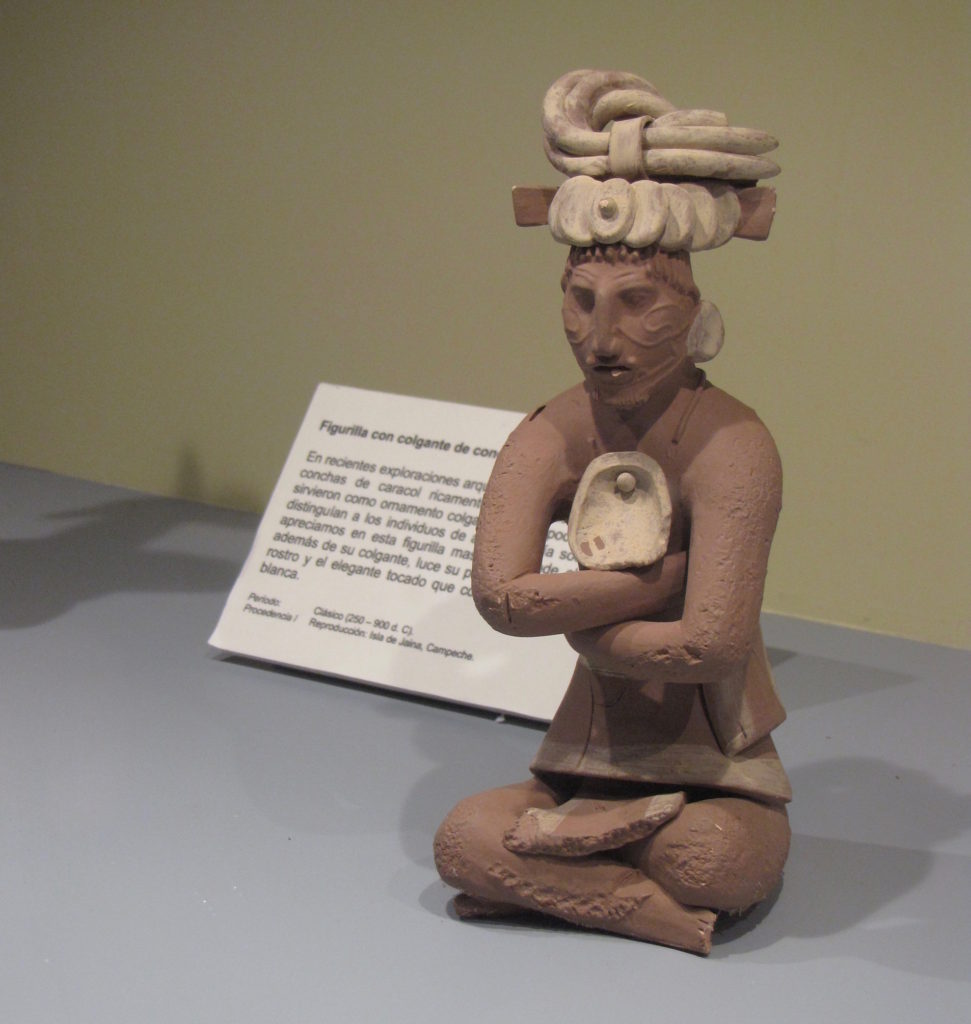

Traversing the distance between the city of Campeche and the hotels surrounding Calakmul takes about four hours, with little in the way of either gas stations or open archaeological sites in between. Over three hours and 150 miles after leaving our hotel we reached our first stop: the partially excavated site of Balamkú. Situated about 30 miles north of Calakmul in the southernmost part of the Maya lowlands, Balamkú was (re)discovered in 1990 and excavations began in 1994. Today, only the central and southern groups have been exposed. A stroll around the grounds reveals a series of attractive but relatively simple ruins picturesquely overgrown with slim, hardy trees and neatly kept by the groundskeeper.

To find Balamkú’s most impressive feature, however, visitors must search a little deeper. We wandered cluelessly for a while before the groundskeeper came up and indicated we should follow him. He led us up a narrow metal staircase alongside one of the site’s larger buildings (Structure 1 of the Central Group), unlocked the door, and ushered us inside. We found ourselves within a long, narrow chamber lit purely by the natural light filtering through a series of small, square holes in the ceiling. To out left stood one of the longest and oldest known painted stucco friezes of the Mayan world.

Stretching 55 ft across, the frieze once included four columns topped by rulers, separated by jaguars or jaguar-like creatures. According to the signage (or at least my questionable translation of the signage), the kingly uppermost figures—of which only one and a half of the original four remain—do not possess any uniquely identifying features and thus likely represented the concept of rulership rather than specific individuals. Each emerges from the jaws of an amphibian—again, according to the INAH sign—representing the fertile aspect of the world. The king’s birth from a creature that can move between water and earth suggests his ability to likewise move between worlds. Each “amphibian” sits upon a mask of the Earth Monster similarly representing the richness of the world while also evoking the four directions.

Jaguars—symbols of sacrifice, war, and death, as well as the risen and subterranean sun—and Jaguar hybrids fill the panels between the masks and provided the inspiration for the site’s current name (balam=jaguar, kú=temple, Balamkú=Temple of the the Jaguar). Taken as a whole, the frieze celebrates and glorifies Balamkú’s rulers and their intimate connection with a healthy and bountiful world.

The INAH website offers a slightly different iconographic summary, suggesting that composition equates the dynastic cycle with the solar cycle. In this view, the image of the ruler emerging from the jaws of the Earth Monster symbolizes his ascension to the throne just as the sun comes out of the earth at dawn, and the ruler’s death is shown at sunset, when he falls back into the Earth’s mouth.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 27, 2015.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 26, 2015.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 26, 2015.

![Venus of Willendorf (Willendorf Figurine) on view at the Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna [original image]](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/DSCN8290-768x1024.jpg)

![Venus of Willendorf (Willendorf Figurine) on view at the Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna [high contrast version]](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/DSCN8290-1-768x1024.jpg)

![Venus of Galgenberg (Stratzing Figure) on view at the Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna [original image]](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/DSCN8292-768x1024.jpg)

![Venus of Galgenberg (Stratzing Figure) on view at the Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna [high contrast version]](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/DSCN8292-1-768x1024.jpg)

![Michelangelo Pistoletto, Ragazzo (Boy) [detail], 1965 and Andy Warhol, Untitled screenprints from the Mao Tse-Tung portfolio, 1972. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz, August 5, 2016. img_8341](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/IMG_8341-1024x768.jpg)