All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, December 2011.

vegetarian in a leather jacket

art, travel, culture

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, December 2011.

Collection-based shows are always problematic because, to an even greater extent than in other exhibitions, the story they tell is limited and skewed by the parameters of a single institution’s holdings. However, every exhibition narrative is necessarily biased, and the particular kind of limitation intrinsic to the collection show is at least upfront and obvious.

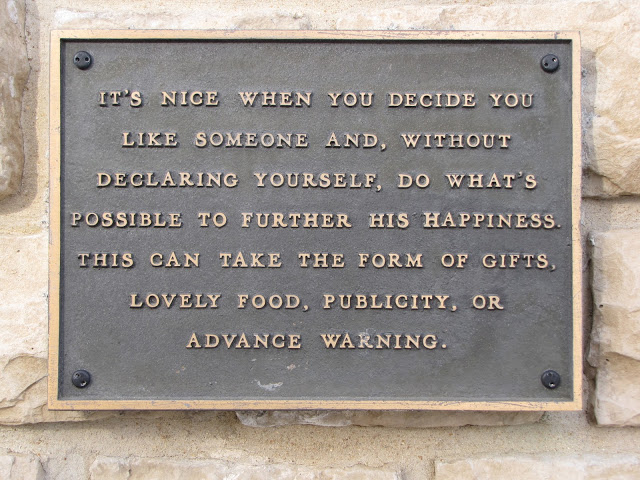

In some instances, these limits can in fact create a useful lens through which to disrupt more familiar stories of an idea or time period. In the case of The Language of Less: Then and Now, currently on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, the all-too-pat historical understanding of “Minimalism” as a masculine, New York-based movement is troubled by the exhibition’s more global and gender-balanced approach.At the same time, both the objects on display and the labels or wall texts accompanying them provide a clear introduction to the ideas behind the push towards simplified forms in the 1960s and beyond that is still broadly referred to as Minimalism. The exhibition (which is split into larger and smaller halves of historical and recent art) therefore offers fertile ground for the thoughts of those already familiar with the history of contemporary art as well as anyone looking for a means of developing an appreciation of Minimalist objects.

Smithson―who is perhaps still best remembered for his earthwork project in Utah’s Great Salt Lake, Spiral Jetty (1970)―is featured prominently in the exhibit with two rarely seen works, Mirror Stratum (above) and an untitled aluminum wall sculpture from the Stenn Family collection. Both pieces exemplify the artist’s interest in the repeated forms which comprise the basis of both natural structures and ancient architecture.

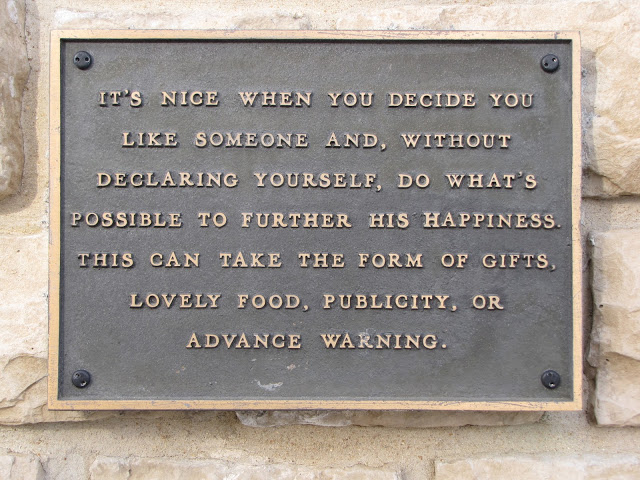

Mirror Stratum, a corner piece consisting of a series of square mirrors stacked in order of decreasing size, is particularly evocative of both the Mayan pyramids and crystalline formations that frequently loomed large in Smithson’s thinking and production. As such, the work exemplifies a kind of Minimalist production based on simple arrangements of repeated, industrially produced objects that manage to poetically suggest a far-reaching range of subject matter.In addition, just as Flavin’s light sculptures (above) command not only the space physically occupied by fluorescent tubing but all of the area filled by their light, Smithson’s stacked mirrors produce a reflected pattern on the wall that extends far above the objects themselves. While this is consistent with a common Minimalist concern with an object’s ability to activate and define the space around it, the effect is also specifically related to what the wall text describes as Smithson’s interest in mirrors as a material that was both “physically present and immaterial, a quality that puts the viewer on heightened alert.”

![Foreground: Alan Sonfist (American, b. 1946), Earth Monument to Chicago, 1965–77 [core samples from beneath the city of Chicago ordered according to color and material]. Background, center: Charlotte Posenenske (German, 1930–85), Series DW Vierkantrohre (Square Tubes), 1967. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/3IMAG0978-1.jpg)

Walther’s fishing net shares the grid aesthetic of classic Minimalism. However, as a found and interactive object dependent on its placement within a gallery space for its status as art, it also possesses a heightened gestural quality that clearly bridges Conceptualism.

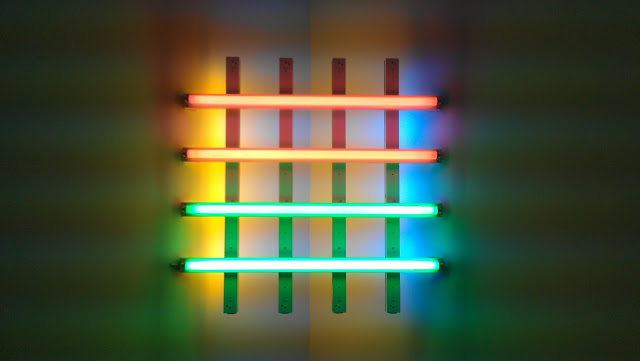

Tuttle also sought an open quality that is lacking in the contemporary production of many of his compatriots working within the Minimalist paradigm. Here, his dyed canvas lacks a clear top or bottom (and front or back) and can be installed anywhere in a room.

One commonality shared by many Minimalist artists is a concern with systems, often represented by the repeated forms of the grid. As noted by the exhibition’s curators, Stuart maintains this interest in “vast systems,” but turns instead to concrete models present in nature rather than the rigid, abstracted form of the grid. The complex, varied surface of Turtle Pond is actually a rubbing of soil, yet it suggests any number of subjects, from the pond of its title to the expanse of the universe.

Although To Underline was made in 1989, its origins lie in the 1960s when Buren began making paintings on striped awning. The found structure imposed by the pre-made stripes (a technique initially explored in the late 1950s by Frank Stella in his Black Paintings) helped to create a unity between individual paintings while drawing attention to the dimensions of each canvas.

![Foreground: Richard Serra (American, b. 1939), Prop, 1968 [lead antimony]. Background: Bruce Nauman (American, b. 1941), Untitled, 1965 [fiberglass and polyester resin]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/9IMAG1008.jpg)

![Carol Bove (American, b. Switzerland, 1971), Polka Dots, 2011 [bronze, steel, concrete, and shells] in front of Harlequin, 2011 [Plexiglas and expanded sheet metal]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/IMAG0901.jpg)

![Carol Bove (American, b. Switzerland, 1971), Untitled, 2011 [peacock feathers on linen]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/IMAG0895.jpg)

![Oscar Tuazon (American, b. 1975; lives and works in France), I gave my name to it, 2010 [steel plate and fluorescent lamps]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/IMAG0918.jpg)

Additionally, The Language of Less compliments the content of the monographic exhibitions currently on view in the museum’s other galleries, including the smaller “MCA DNA” shows dedicated to Gordon Matta-Clark and Dieter Roth, both of whose works from the 1970s are indebted to ideas which had started to percolate the decade before.The introduction to Minimalism outlined in The Language of Less provides a particularly helpful background for the exhibit dedicated to Canada’s Iain Baxter& (b. Iain Baxter, United Kingdom, 1936), whose often humorous objects and installations are clearly rooted in the movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Indeed, many of his works poke fun at the production of his contemporaries or recent predecessors, and so make little sense without a background in other artists of that period.

![IT (collaborative name of Baxter, Elaine Hieber, and John Friel), Extended Noland, 1966 [velvet ribbon on fabric]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/IMAG1032-1.jpg)

![IT, Pneumatic Judd, 1965 [inflated vinyl]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/IMAG1033.jpg)

![Iain Baxter&, Television Works, 1999–2006 [Acrylic paint on reclaimed televisions; reclaimed pedestals and reclaimed metal wall brackets]. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/IMAG1028-1.jpg)

Go to http://mcachicago.org/exhibitions/now for a list of the MCA’s current exhibitions and links to their descriptions.

I’m currently working on a review of the MCA’s exhibition, The Language of Less: Then and Now, and am putting together the next part of the Modern and Contemporary bibliography. In the meantime, here are some images from the past week.

All photos are by me unless otherwise indicated.