Once again, this bibliography should be understood as in-progress. There are currently some important holes, the most obvious and serious being Fluxus as well as the recent arts of China and Latin America. I hope to add these later.

In addition to checking out some or all of the following books and essays, the most helpful thing anyone can do in increasing their understanding of modern and contemporary art is to go to exhibitions and read the wall labels.

General

Lynn Gamwell. Exploring the Invisible: Art, Science, and the Spiritual. Princeton University, 2002.

This book begins in the mid-19th century and concludes in the early 20th century. It is a great alternative to a regular survey book for those who are particularly interested in the role of science in Modern art. [also listed in the 19th century bibliography]

Nicholas Mirzoeff. “The Multiple Viewpoint: Diaspora and Visual Culture,” in The Visual Culture Reader, Second Edition. Edited by Nicholas Mirzoeff. Routledge, 2002. 204–214.

Helen Molesworth. Part Object, Part Sculpture. Wexner Center for the Arts, 2005.

Alex Potts. The Sculptural Imagination: Figurative, Modernist, Minimalist. Yale, 2000.

This beautifully produced book covers a broad range of sculpture, but focuses primarily on Western productions from the 20th century. Although the writing is clear enough for the casual reader, the content, which deals with the shifting philosophical underpinnings of sculpture, is more complex than most historical or stylistic surveys.

Joan Rothfuss and Elizabeth Carpenter. Bits and Pieces Put Together to Present a Semblance of a Whole: Walker Art Center Collections. Walker Art Center, 2005.

As one of the pre-eminent museums for contemporary art in the United States, the Walker’s collection catalogue reads as a who’s-who in contemporary art, up to the date of publication. Although not every included artist is equally well represented, the catalogue nonetheless serves as a good introduction to the variety of contemporary practices.

Essay Collections

Hal Foster. The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century. MIT Press, 1999.

Salah Hassan and Iftikhar Dadi (eds). Unpacking Europe: Towards a Critical Reading. NAi, 2001.

Among other things, this exhibition catalogue and essay collection serves as a critique of, and counter-point to, the canonical narrative of Western Art.

Rosalind Krauss. Passages of Modern Sculpture. MIT, 1977.

This is a definitive collection of essays and should be read (critically) by anyone with a serious interest in Modern art.

Primitivism

William Rubin. Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern. The Museum of Modern Art, 1984.

See also: Thomas McEvilley. Artforum 23 (November 1984): 54–61 and Artforum 28 (March 1990): 19–21. [Artforum essays in Flam and Deutch, Primitivism and 20th Century Art: A Documentary History]

AUSTRIA

Turn-of-the-century Vienna: Secession, Expressionism, and the Wiener Werkstätte

Compared to contemporary movements in France and Germany, Viennese artists are under-represented outside of Austria. For those interested in this period, the small but excellent Neue Museum in New York has a solid collection of art and design, and also periodically hosts related temporary exhibitions. Otherwise, Vienna is the place to go.

Elisabeth Schmuttermeier and Christian Witt-Dörring (eds). Postcards of the Wiener Werkstätte: A Catalogue Raisonné (Selections from the Leonard A. Lauder Collection). Neue Museum, 2010.

Kirk Varnedoe. Vienna 1900: Art, Architecture and Design. The Museum of Modern Art, 1986.

Peter Vergo. Art in Vienna, 1898–1918: Klimt, Kokoschka, Schiele and Their Contemporaries. Phaidon, 1975.

Viennese Actionists (1960s)

There are even fewer resources on the Viennese Actionists in the US. Exhibitions and other resources are more common in Europe, particularly Austria.

Museum Hermann Nitsch. Hatje Cantz, 2008.

Stephen Barber. The Art of Destruction: The Films of the Vienna Action Group. 2004.

Malcolm Green. Writings of the Vienna Actionists. Atlas, 1999.

FRANCE

Fauvism and Matisse

John Elderfield. The Wild Beasts: Fauvism and its Affinities. The Museum of Modern Art, 1976.

There are larger, more recent books on Fauvism, but Elderfield’s slim volume is still a useful and accessible introduction.

John Elderfield. Henri Matisse: A Retrospective. The Museum of Modern Art, 1992.

Cubism

T. J. Clark, “Cubism and Collectivity,” in Farewell to an Idea. Yale, 1999.

William Rubin, et al. Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism. The Museum of Modern Art, c. 1989.

Brancusi

A number of museums around the country possess works by Brancusi. However, some of the best collections are to be found at The Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Friedrich Teja Bach, Margit Rowell, and Ann Temkin. Constantin Brancusi. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1995.

If you read one book on Brancusi, this should be it. An excellent and far-reaching catalogue of the sculptor’s production.

Athena Spear. Brancusi’s Birds. New York University, 1969.

A closer look at one of Brancusi’s most discussed series of sculpture, covering related topics ranging from Romanian folklore to the importance of the base.

Purism

See also the “Europe Between the Wars” section, below, for related materials.

Kenneth Silver, “Purism: Straightening Up After the Great War,” Artforum 15 (March 1977): 56–63.

There are good books on the subject of Purism, but Silver’s article outlines the basics and is probably all most people will need.

GERMANY AND RUSSIA

Kandinsky, the Blaue Reiter, and the Blue Four

Kandinsky. Guggenheim, 2009.

A well-illustrated catalogue and good survey of Kandinsky’s work.

Vivian Endicott Barnett and Josef Helfenstein (eds). The Blue Four: Feininger, Jawlensky, Kandinsky, and Klee in the New World. Dumont, 1997.

Wassily Kandinsky. Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Translation and introduction by M.T.H. Sadler. Dover, 1977 [1914].

Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc. The Blaue Reiter Almanac, Documents of 20th-Century Art. Viking, 1974 [1965].

German Art Before and After WWI: Expressionism and Neue Sachlichkeit

See also “Dada” section for other relevant readings.

Max Beckmann. Self-Portrait in Words: Collected Writings and Statements, 1903–1950. Edited by Barbara Buenger. University of Chicago, 1997.

Maud Lavin. Cut with the Kitchen Knife: The Weimar Photomontages of Hannah Hoch. Yale, 1993.

Jill Lloyd. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Royal Academy of Arts, 2003.

This monograph on Kirchner also serves as an accessible introduction to German Expressionism.

Olaf Peters. Otto Dix. Neue Galerie, 2010.

Sabine Rewald, Ian Buruma, and Matthias Eberle. Glitter and Doom: German Portraits from the 1920s. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007.

Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1919–1933: Workshops for Modernity. The Museum of Modern Art, 2009.

Walter Gropius. “The Theory and Organization of the Bauhaus [1923],” in Art in Theory: 1900–1990. Blackwell, 1993. 130–135.

Russia: Suprematism and Constructivism

I am still waiting for a single accessible, informative, and enjoyable text on Constructivism. However, the movement is too important to the development of later art to exclude.

Yve-Alain Bois. “Lissitsky’s Radical Reversibility,” Art in America 76, 4 (April 1988). 160–181.

Briony Fer. “Metaphor and Modernity: Russian Constructivism,” Oxford Art Journal 12, 1 (1989). 14–30.

Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner. “The Realistic Manifesto,” in The Tradition of Constructivism. Edited by Stephen Bann. Da Capo, 1974.

Maria Gough. “Faktura: The Making of the Russian Avant-Garde,” Res 36 (Autumn 1989). 32–59.

Nina Gurianova, et al. Kasimir Malevich: Suprematism. Guggenheim, 2003.

Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (eds). Art in Theory: 1900–1990. Blackwell Press, 1992. See the manifestos on pages 308–330.

Christina Lodder. Russian Constructivism. Yale, 1984.

Victor Margolin. The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy: 1917–1946. University of Chicago, 1997.

Margarita Tupitsyn. “From the Politics of Montage to the Montage of Politics: Soviet Practice 1919 through 1937,” in Montage and Modern Life: 1919–1942. MIT, 1992.

NETHERLANDS

Mondrian and De Stijl

De Stijl, 1917–31: Visions of Utopia. Walker Art Center, 1981.

Yve-Alain Bois and Angelica Rudenstine. Mondrian: 1872–1944. National Gallery of Art, 1995.

Nancy Troy. The De Stijl Environment. MIT, 1983.

ITALY

Futurism

Italian Futurism 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe. Guggenheim, 2014.

Umbro Apollonio (ed). Futurist Manifestos. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1973.

See especially the manifestos by Marinetti and Boccioni.

Rosalind Krauss. “Analytic Space: Futurism and Constructivism,” in Passages of Modern Sculpture. MIT, 1977.

Christine Poggi. Inventing Futurism: The Art and Politics of Artificial Optimism. Princeton University, 2009.

Caroline Tisdall and Angelo Bozzolla. Futurism. Thames and Hudson, 1977.

JAPAN

MAVO

Gennifer Weisenfeld. MAVO: Japanese Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1905–1931. University of California, 2001.

Alexandra Munroe. Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky. Harry N. Abrams, 1994.

INTERNATIONAL MODERNISM

Although Futurism, Cubism, and the Bauhaus gathered together multinational artists or had ramifications outside their countries of origin, they are each still largely associated with Italy, France, and Germany, respectively. In contrast, the following movements are intrinsically international and should be understood as such.

Europe Between the Wars: “The Return to Order”

Emily Braun, et al. Chaos and Classicism: Art in France, Italy and Germany, 1918–1936. Guggenheim, 2011.

Kenneth Silver. “Matisse’s Retour à l’ordre,” Art in America (June 1987), 110–123ff.

Dada

Dorothea Dietrich, et al. Dada: Zurich, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, New York, Paris. DAP, 2008.

William A. Camfield, Marcel Duchamp: Fountain. The Menil Collection, 1989. 13–61.

Molly Nesbit. “The Language of Industry,” in The Definitively Unfinished Marcel Duchamp. Edited by Thierry de Duve. MIT, 1991. 351–384.

Surrealism

André Breton. Manifestoes of Surrealism. Translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. University of Michigan, 1969.

See especially “Manifesto of Surrealism” (1924) and “Second Manifesto of Surrealism” (1930).

Hal Foster. Compulsive Beauty. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993.

Rosalind Krauss and Jane Livingston. L’Amour fou: Photography and Surrealism. Arts Council of Great Britain, 1986.

Frances Morris (ed). Louise Bourgeois. Rizzoli, 2008.

Jennifer Mundy (ed). Surrealism: Desire Unbound. Tate, 2001.

Michael R. Taylor. Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2009.

This exhibition catalogue focuses on Duchamp’s last and most Surrealistic work, Étant donnés, as well as its relevant context and legacy. Made secretly over the course of 20 years while Duchamp was an ex-patriot in New York, this sculptural installation is well worth the kind of deep analysis it receives here and is an excellent jumping-off point for a broader understanding of Surrealism and Surrealist circles in New York.

AMERICA

Stephanie Barron and Sabine Eckmann. Exiles + Emigrés: The Flight of European Artists from Hitler. LACMA, 1997.

Abstract Expressionism

Emile de Antonio. Painters Painting (1972) [DVD 2010]

Serge Guilbaut. How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom, and the Cold War. University of Chicago Press, 1983.

Michael Leja. Reframing Abstract Expressionism: Subjectivity and Painting in the 1940s. Yale, 1993.

Ann Temkin (ed). Barnett Newman. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2002.

Stephanie Terenzio (ed). The Collected Writings of Robert Motherwell. University of California, 1999.

Jeffery Weiss. Mark Rothko. National Gallery of Art, 1998.

Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg: Between AbEx and Pop

Paul Schimmel (ed). Robert Rauschenberg: Combines. Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 2005.

Jeffery Weiss. Jasper Johns: An Allegory of Painting, 1955–1965. National Gallery of Art, 2007.

Los Angeles

See also The Rise of the Sixties under “Art of the 1960s and 70s.”

Robin Clark (ed). Phenomenal: California Light, Space, Surface. University of California, 2011.

Rebecca Peabody, et al. Pacific Standard Time: Los Angeles Art, 1945–1980. Getty, 2011.

Native American (U.S. and Canada)

The Spirit Within: Northwest Coast Art from the John H. Hauberg Collection. Seattle Art Museum, 1995.

In this context, I especially recommend Nora Marks Dauenhauer’s essay, “Tlingit At.óow: Traditions and Concepts,” as a window into the role of tradition and traditional objects in Tlingit culture.

Janet C. Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips. “The Twentieth Century: Trends in Modern Native Art,” in Native North American Art. Oxford University, 1998. 208–239.

The line between “Modern” and “Contemporary” art is blurred here, but the emphasis in this chapter is primarily on works that are more in keeping with broader “Contemporary” practices.

Peter Macnair, Alan Hoover, and Kevin Neary. The Legacy: Tradition and Innovation in Northwest Coast Indian Art. University of Washington, 1984.

INTERNATIONAL CONTEMPORARY ART

Africa and the diaspora

See also the “1980–2010: A few biased selections” section for additional readings.

Okwui Enwezor. The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945–1994. Prestel, 2001.

N’Goné Fall and Jean Loup Pivin. An Anthology of African Art: The Twentieth Century. DAP, 2002.

Shannon Fitzgerald and Tumelo Mosaka. A Fiction of Authenticity: Contemporary Africa Abroad. Contemporary Art Museum Saint Louis, 2003.

The “Return of the Real” in Art of the 1960s and 1970s: Minimalism, Pop, Land Art, Conceptualism, Performance, and their legacies

See also the “Viennese Actionists” section [above].

Donald Judd’s Marfa, Texas/Tony Cragg: In Celebration of Sculpture [2006, DVD].

Richard Serra: The Matter of Time. Bilbao: Guggenheim, 2005.

Thomas Crow. The Rise of the Sixties: American and European Art in the Era of Dissent. Harry N. Abrams, 1996.

Corinne Diserens (ed). Gordon Matta-Clark. Phaidon, 2003.

See especially the text by Thomas Crow, pages 7–132.

Jack Flam (ed). Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings. University of California, 1996.

Laura Hoptman, Akira Tatehata, and Udo Kultermann. Yayoi Kusama. Phaidon, 2000.

Covers Kusama’s career from the late 1950s through the 1990s.

Stephen Koch. Stargazer: Andy Warhol’s World and His Films, Second Edition. New York: Marion Boyars, 1985.

Daniel Marzona. Conceptual Art. Taschen, 2006.

A slim and inexpensive volume that offers a good introduction to Conceptual Art and several of the movement’s most notable artists. Consists of a brief historical overview in the introductory essay followed by a series of 2-page spreads, each focusing on a signature work by artists like Marcel Duchamp, Mel Bochner, and Ana Mendieta.

*James Meyer. Minimalism. Phaidon, 2010.

This is an abbreviated version of Meyer’s 2001 book, Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties. Informative, well-illustrated, and to-the-point; highly recommended.

Pamela M. Lee. Chronophobia: On Time in the Art of the 1960s. MIT, 2006.

Anne Rorimer. New Art in the 60s and 70s: Redefining Reality. Thames and Hudson, 2001.

Mark Rosenthal. Joseph Beuys: Actions, Vitrines, Environments. Tate, 2004.

Elizabeth Sussman (ed). Eva Hesse. SFMoMA, 2002.

Elizabeth Sussman and Fred Wasserman. Eva Hesse: Sculpture. The Jewish Museum, 2006.

Although shorter and more limited in scope than the SFMoMA catalogue, Eva Hesse: Sculpture has the advantage of being more easily available than the previous publication, while focusing on Hesse’s most iconic works through a collection of well-illustrated, thoughtful essays.

Eugenie Tsai and Cornelia Butler. Robert Smithson. Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 2004.

See especially Moira Roth’s interview with Smithson (p. 80-94) and the essays by Thomas Crow and Jennifer Roberts (p. 32-56 and p. 96-103, respectively).

Paul Wood. Conceptual Art. Tate, 2002.

Another slim volume which takes a broad view of conceptual art, and would perhaps be better titled, The Conceptual Basis of Contemporary Art. Regardless, it is a very good introduction to contemporary productions in Europe and the Americas during the 1960s and 1970s.

1980–2010: A few biased selections

In addition to the below, which are mostly monographs, I also find biennial catalogues to be useful references for the major concepts, concerns, and artists of their times. The Venice Biennale is the oldest and most famous of the biennials, and its catalogues are also the easiest to come by. The 1997 Johannesburg Biennial was a pivotal exhibition, both intellectually and politically, but the catalogue is more difficult to find. A review by Carol Becker, originally published in Art Journal, can be found online via Google Books as part of her book, Surpassing the Spectacle.

For those interested in watching artists talk about their work, the Art:21 series—which covers a range of themes and methods from the 21st century—is also very informative. It is available on DVD.

Daina Augaitis. Brian Jungen. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 2005.

Jack Bankowsky, Alison M. Gingeras, and Catherine Wood (eds). Pop Life: Art in a Material World. Tate, 2009.

Rainer Crone and Petrus Graf Schaesberg. Louise Bourgeois: The Secret of the Cells. Prestel, 2008.

Thierry de Duve. Jeff Wall: Complete Edition. Phaidon, 2010.

Okwui Enwezor, et al. Contemporary African Art Since 1980. Bologna: Damiani, 2009.

Dana Friis-Hansen, et al. Outbound: Passages from the 90’s. Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, 2000.

This well-illustrated catalogue includes short but incisive texts on some of the most sustaining artists of the 1990s (and today), including Janine Antoni, Matthew Barney, Cai Guo-Qiang, Robert Gober, Ann Hamilton, Jim Hodges, William Kentridge, Shirin Neshat, and Fred Wilson.

Ann Goldstein. Barbara Kruger. Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1999.

Eleanor Heartney. Roxy Paine. Prestel, 2009.

Jeff Koons, et al. Jeff Koons. Taschen, 2009.

Takashi Murakami. Super Flat. MADRA, 2000.

Louise Neri (ed). Looking Up: Rachel Whiteread’s Water Tower. Scalo, 1999.

An in-depth look at one of Whiteread’s major works. Highly recommended.

Norman Rosenthal. Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection. Thames and Hudson, 1998.

There has been a lot written on individual YBA artists—including Damian Hirst, Tracey Emin, and Yinka Shonibare—but this is the exhibition that introduced most of them to the US. It is also the exhibition that sparked serious discussion and controversy about public funding and censorship in the arts.

Paul Schimmel (ed). ©Murakami. Rizzoli, 2007.

Nancy Spector. Matthew Barney: The Cremaster Cycle. Guggenheim, 2002.

Chris Townsend. The Art of Rachel Whiteread. Thames and Hudson, 2004.

A solid overview of Whiteread’s work up to the date of publication, approximately the first decade of her career.

Interviews, Novels, and Other Writings by Artists, Critics, and Philosophers

Georges Bataille. Story of the Eye. City Lights Books, 1987 [1928].

This is Bataille’s first novel and represents a particularly dark (but illustrative) form of Surreal pornography.

Walter Benjamin. “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility (Second Version),” in The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media, by Walter Benjamin. Edited by Brigid Doherty, Michael W. Jennings, and Thomas Y. Levin. Harvard University Press, 2008. 19–55.

H. P. Blavatsky, The Key to Theosophy. Wheaton: Quest, 1972 [1889]

Emerging near the end of the 19th century, Theosophy was important to a number of early 20th century artists, including Kandinsky, Mondrian, Kupka, and the Futurists. This abridged version of The Key to Theosophy may be useful to those who want a better understanding of one of the philosophical influences of the period or a peek into the zeitgeist of the late 1800s.

Louise Bourgeois. Destruction of the Father, Reconstruction of the Father: Writings and Interviews 1923–1997. MIT Press, 1998.

Andre Breton. Nadja. Translated by Richard Howard. Grove Press, 1960 [1928].

Breton was the founder of the Surrealist movement. This autobiographical novel about his encounter and affair with an unstable woman epitomizes the often troubling gender dynamics of Surrealism.

Michael Fried. Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews. University of Chicago, 1998.

See especially “Art and Objecthood (1967),” which critiques Minimalism with a focus on Morris and Judd. Judd’s response to this essay is also an iconic text and represents an important counter-point to Fried’s claims.

Clement Greenberg. Art and Culture. Beacon, 1961.

See especially “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (p. 3-21).

Ernest Hemingway. A Moveable Feast. Scribner, 2003 [1964].

Hemingway’s account of his time in Paris in the 1920s.

D.H. Lawrence. Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Penguin, 2006 [1928].

Banned in England and the US at the time of its original publication, Lady Chatterley’s Lover vividly illustrates the appeal of primitivism during the early 20th century and its relationship to the changing social landscape brought on by the Industrial Revolution.

Hans Ulrich Obrist. Interviews, Volume 1. Charta, 2003.

Obrist’s list of interviewees reads like a who’s who of contemporary artists, and the interviews themselves are informative.

Gertrude Stein. The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Vintage, 1990 [1933].

Despite its name, this is Stein’s own auto-biography written through the eyes of her partner, Alice B. Toklas. As an avant-garde collector and writer, Stein became close to modern figures such as Ernest Hemingway and Pablo Picasso, and her home in Paris often served as a hub for modern artists in the early 20th century.

Unica Zürn. The House of Illnesses. Translated by Malcolm Green. Atlas, 1993 [1977].

Unica Zürn became associated with Surrealist circles through her relationship with Hans Bellmer. This is an illustrated excerpt from Zürn’s Man of Jasmine, and serves as an account of her time in a hospital during a jaundice-induced fever.

![Nine Dragon Screen [detail], Datong. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/IMG_4948-1.jpg)

![Pablo Picasso, Half-Length Female Nude [detail], 1906. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/2IMG_2639.jpg)

![Amedeo Modigliani, Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz [detail of Berthe], 1916. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/3IMG_2676.jpg)

![Jacques Lipchitz, Seated Figure [detail], 1917. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/12IMG_2697.jpg)

![Alberto Giacometti, Diego Seated in the Studio [detail], 1950. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/13IMG_3038.jpg)

![Alberto Giacometti, Walking Man II [detail], 1960. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/14IMG_3040.jpg)

![Henri Matisse, Lorette with Cup of Coffee [detail], 1916–17. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/17IMG_2819.jpg)

![Matta, Untitled (Flying People Eaters) [detail], 1942. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/26IMG_2959.jpg)

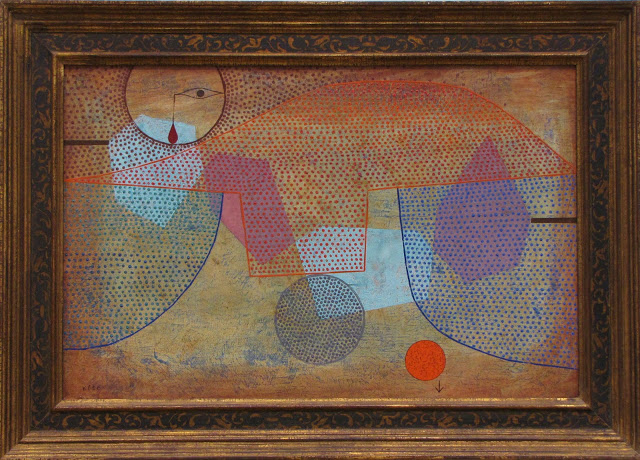

![Max Ernst, Spanish Physician [detail], 1940. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/27.1IMG_2994.jpg)

![Oskar Kokoschka, Commerce Counselor Ebenstein [detail], 1908. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/29IMG_2724.jpg)

![Franz Marc, The Bewitched Mill [detail], 1913. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/30IMG_2741.jpg)

![Henri Matisse, Woman before an Aquarium [detail], 1921–23](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/35IMG_2814.jpg)

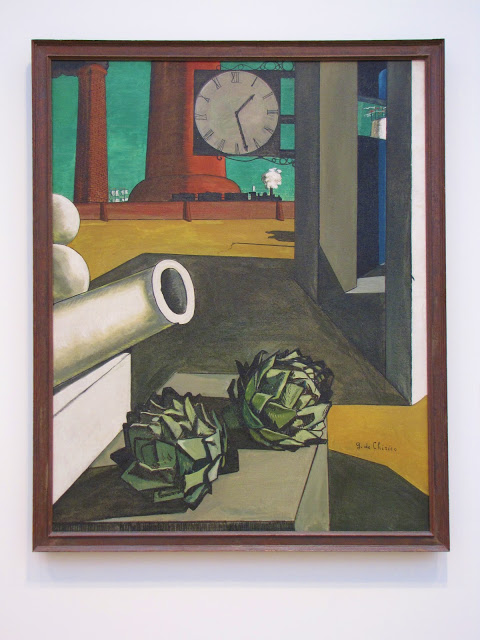

![Giorgio de Chirico, The Eventuality of Destiny [detail], 1927. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/36IMG_2829.jpg)

![Yves Tanguy, The Rapidity of Sleep [detail], 1945. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/38IMG_2869.jpg)

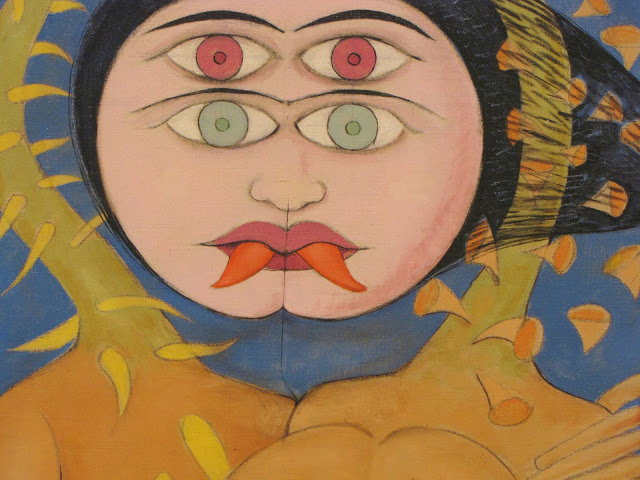

![Joan Miró, Woman [detail], 1934. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/41IMG_2939.jpg)

![Aleksei Alekseevich Morgunov, Portrait of Nathalija Gontcharova and Mihajl Larionov [detail of Gontcharova], 1913. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/47IMG_2702.jpg)

![Ludwig Meidner, Max Herrmann-Neisse [detail], 1913. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/49IMG_2759.jpg)

![Le Corbusier, Untitled [detail], 1932. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/50IMG_2825.jpg)

![Leonora Carrington, Juan Soriano de Lacandón [detail], 1964. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/51.2IMG_2925.jpg)

![Max Beckmann, Self-Portrait [detail], 1937. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/52IMG_2851.jpg)

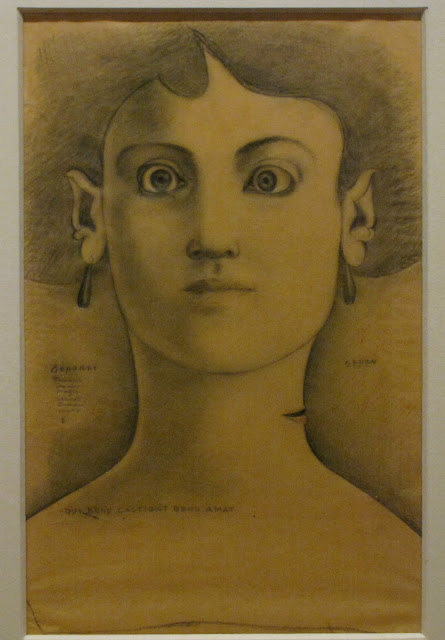

![John D. Graham, Apotheosis [detail], 1955-57. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/54IMG_2948.jpg)

![Matta, The Earth Is a Man [detail], 1942. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/55IMG_3050.jpg)

![Joan Miró, Two Personages in Love with a Woman [detail of woman], 1936. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/56IMG_3017.jpg)

![Matta, Untitled (Flying People Eaters) [detail], 1942. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/57IMG_2949.jpg)

![Salvador Dalí, Venus de Milo with Drawers [detail], 1936. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/58.1IMG_2980.jpg)

![Pablo Picasso, The Red Armchair [detail], 1931. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/58IMG_2842.jpg)

![Salvador Dalí, A Chemist Lifting with Extreme Precaution the Cuticle of a Grand Piano [detail], 1936. Photo by Renée DeVoe Mertz.](https://www.vegetarianinaleatherjacket.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/64IMG_2974.jpg)