Between Dzibilchaltún and Mérida’s city center sits the strikingly contemporary building of the Gran Museo del Mundo Maya. Built in 2012 in the shape of an abstracted ceiba tree (which in Maya mythology unites the three levels of the world), the museum expertly combines a vast collection of artifacts with up-to-date technology and display techniques, including immersive, multi-channel animations.

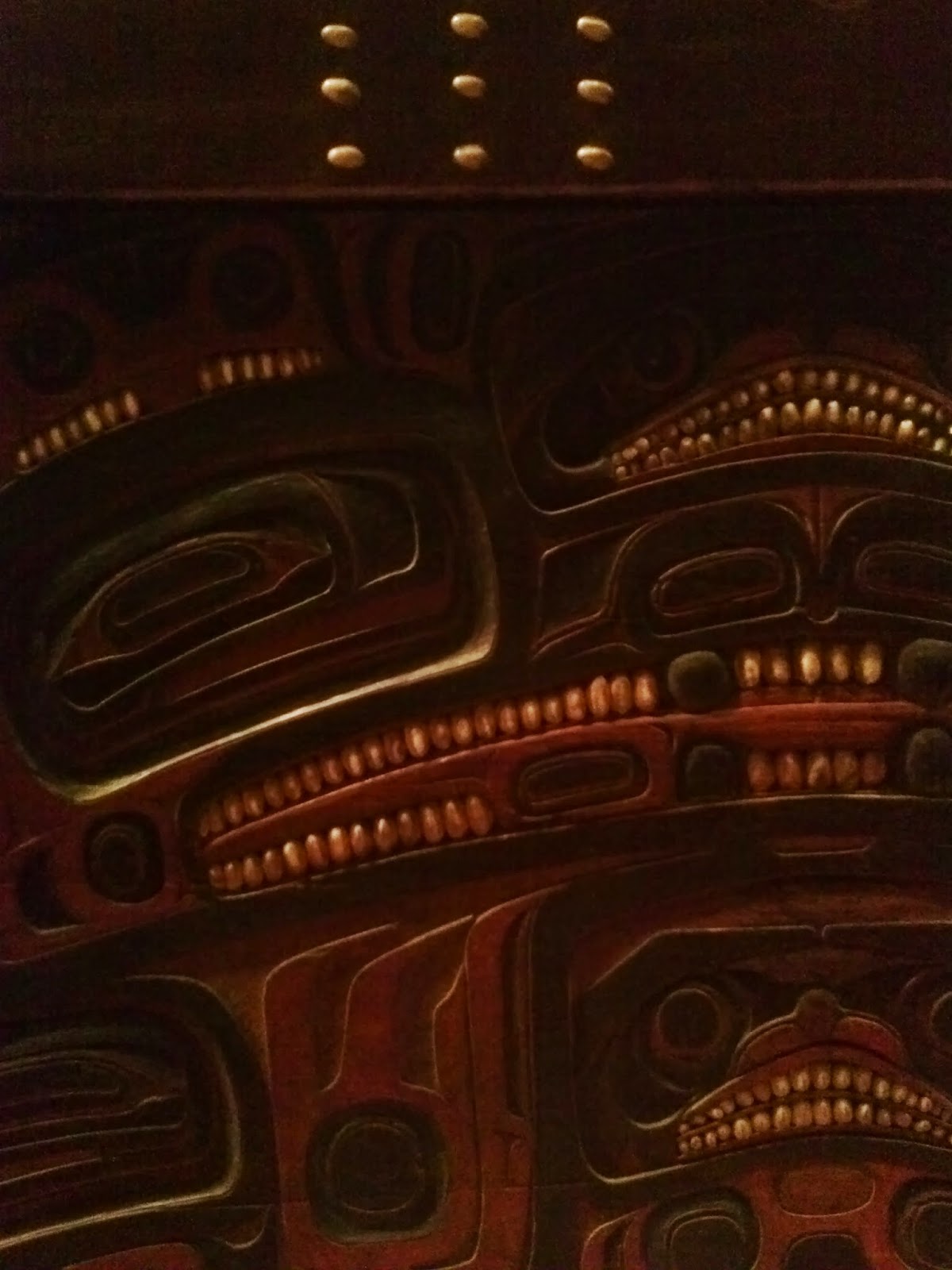

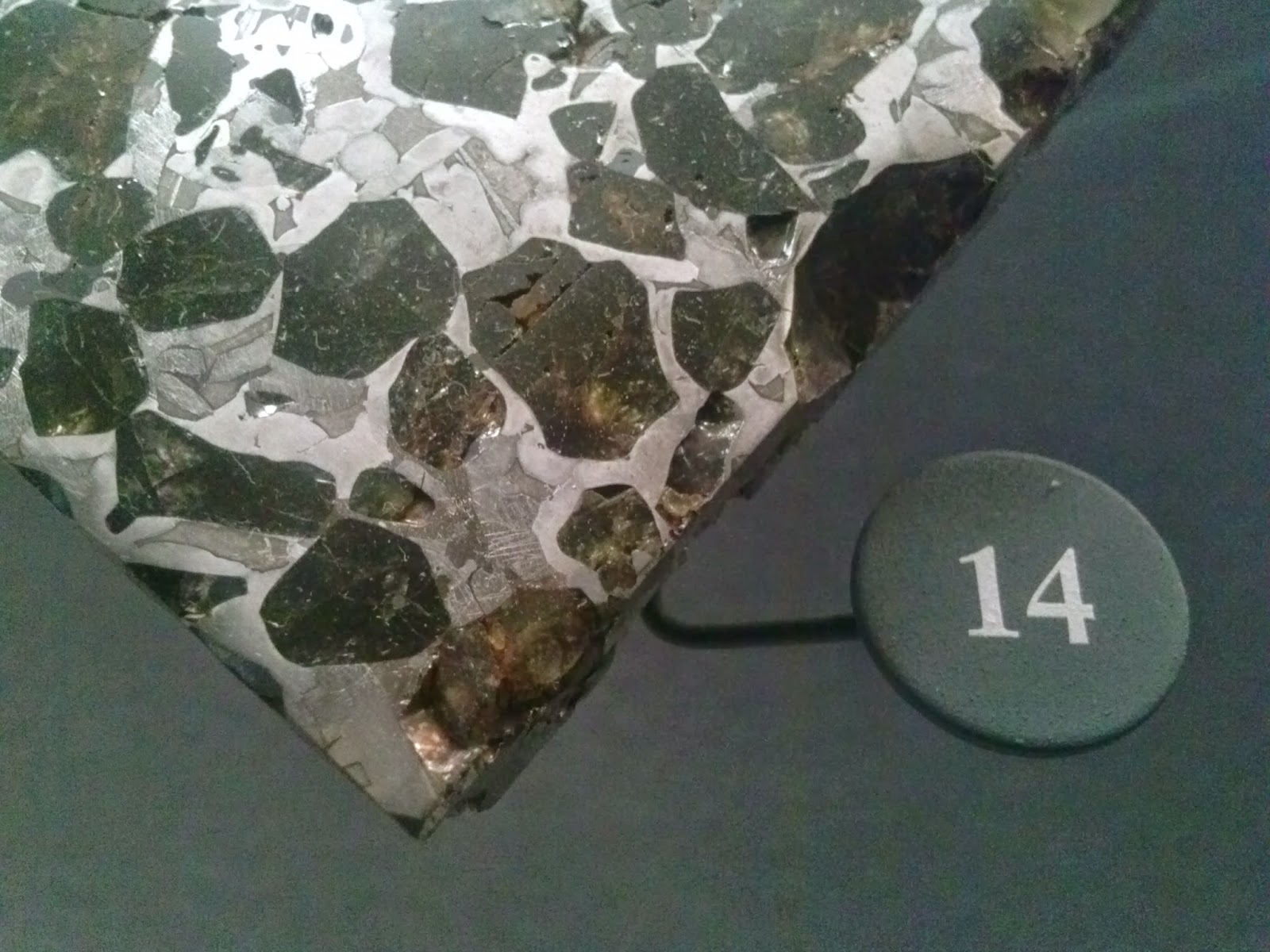

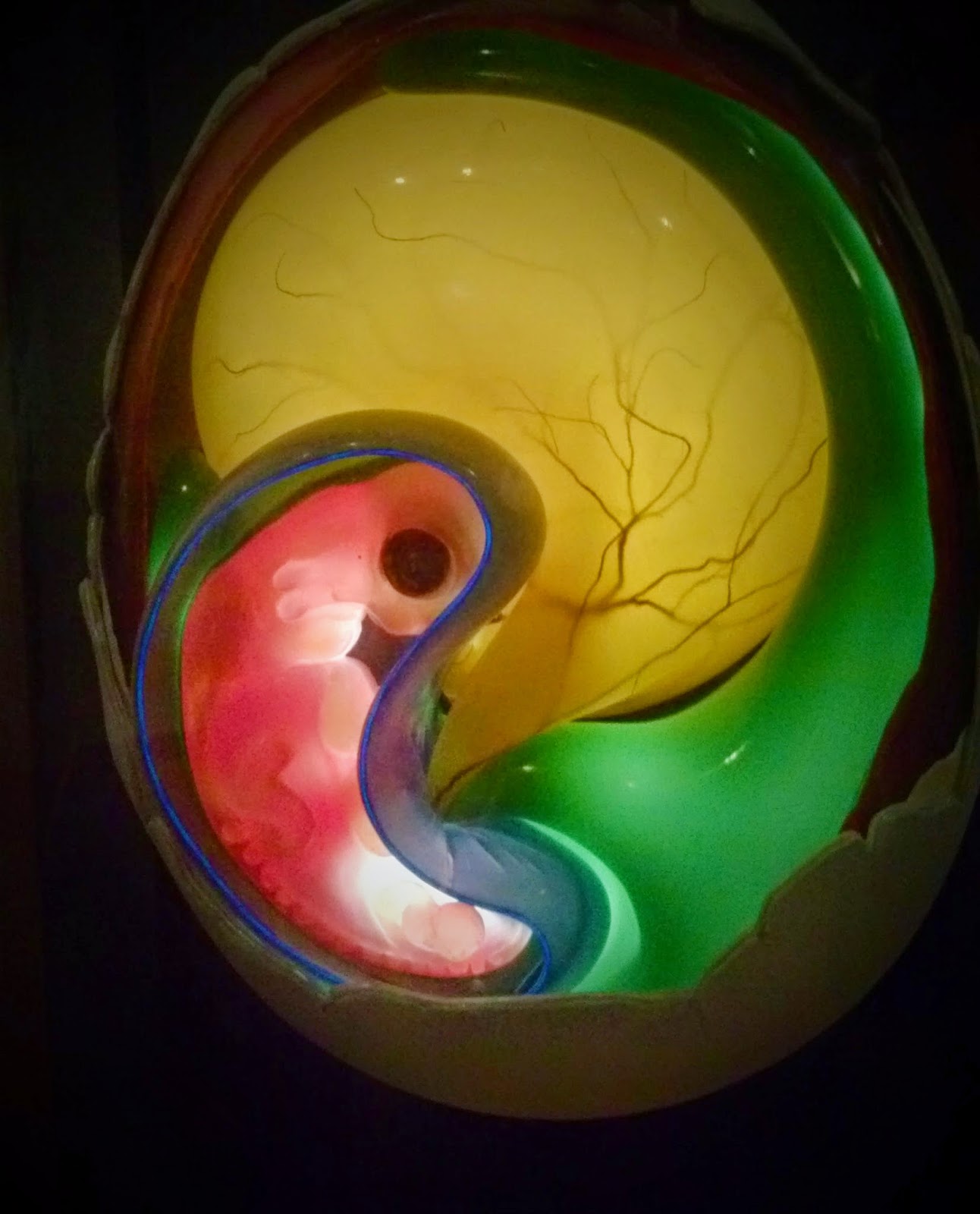

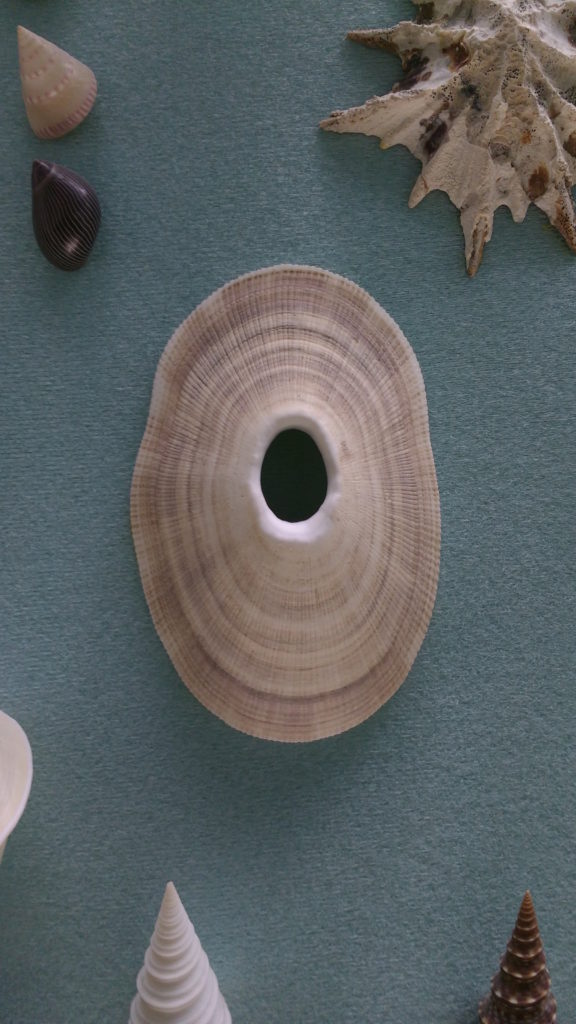

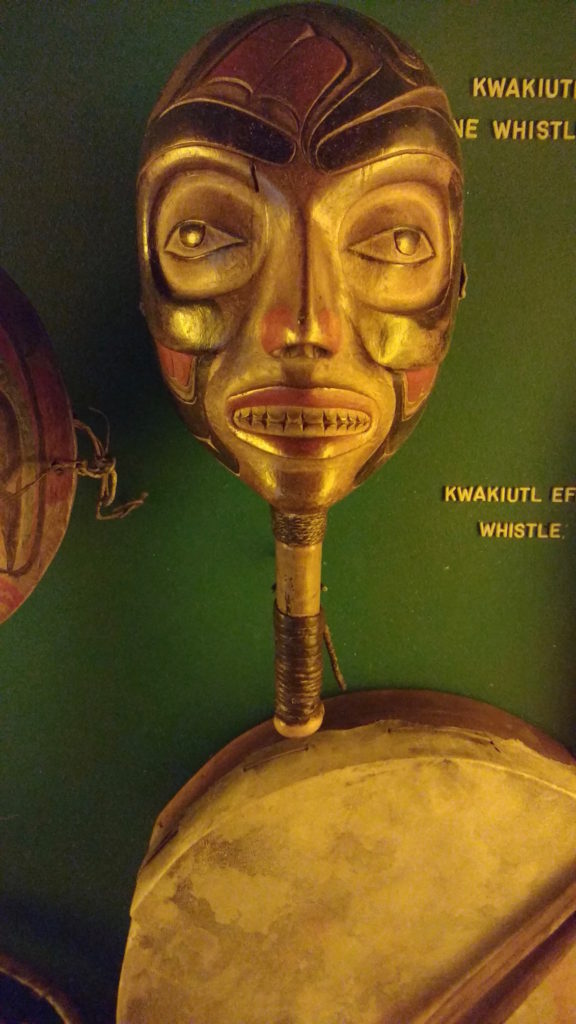

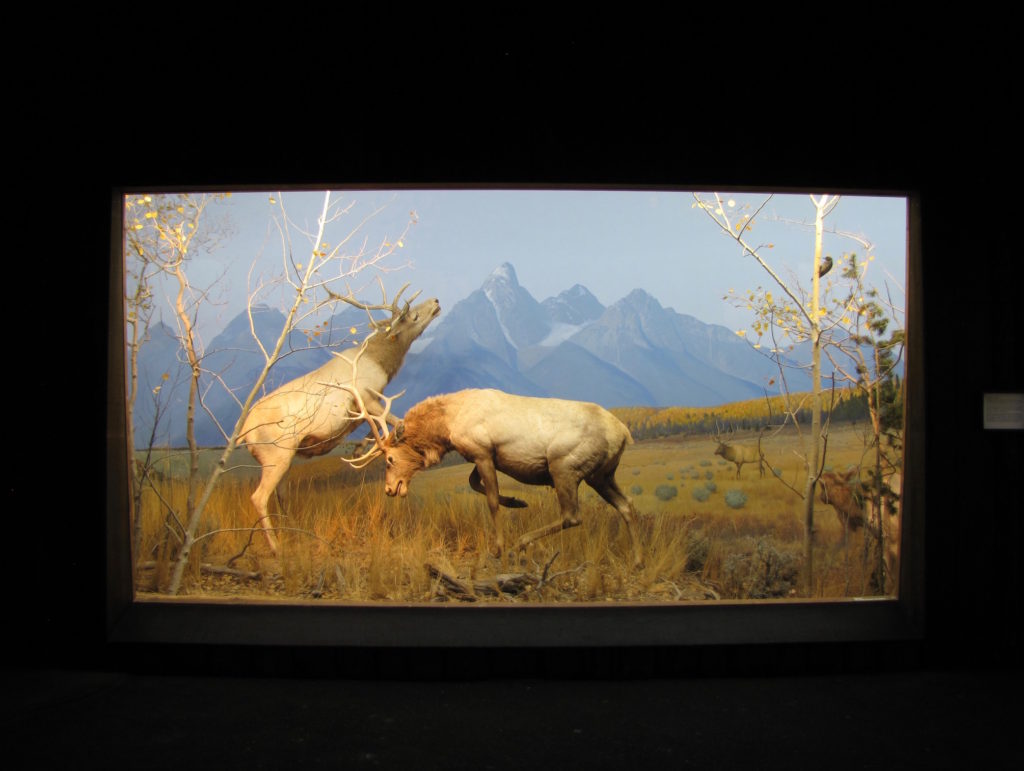

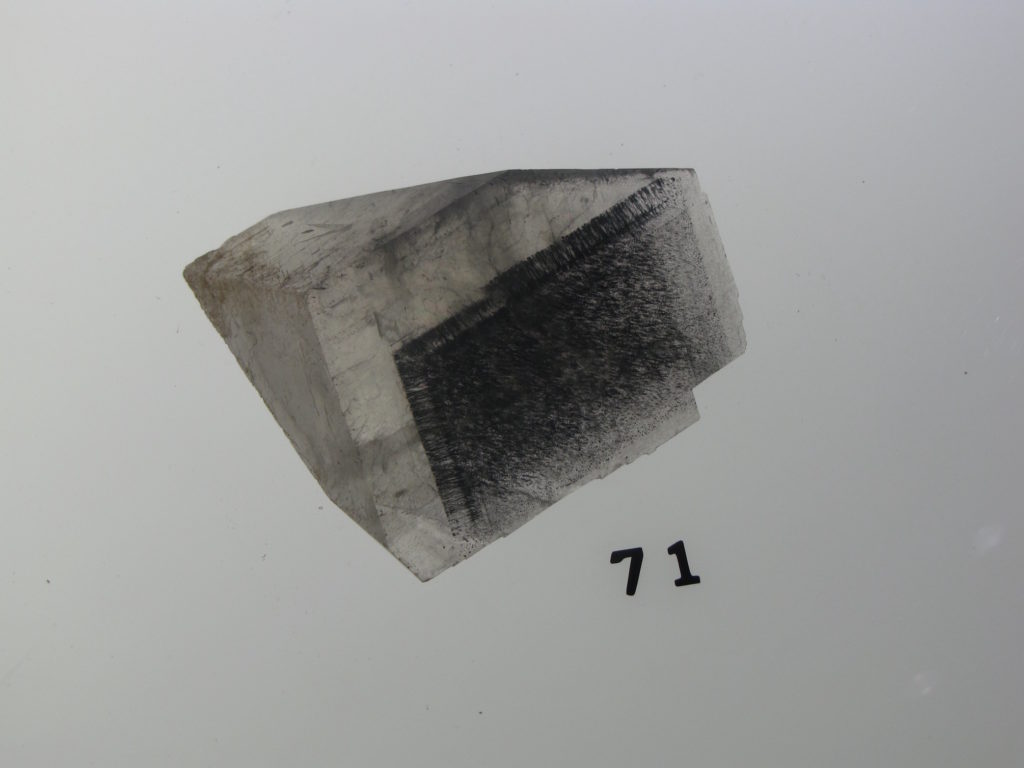

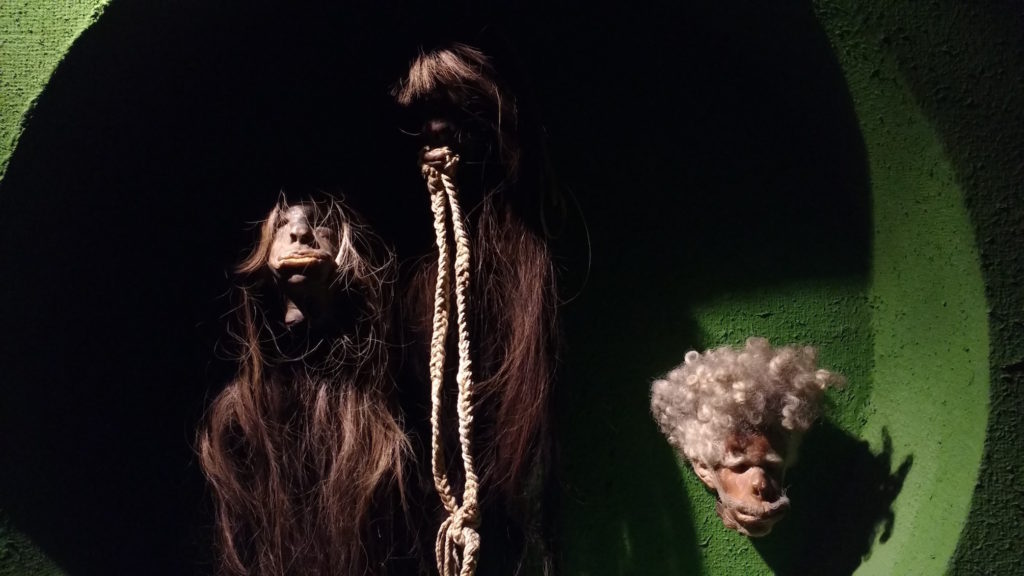

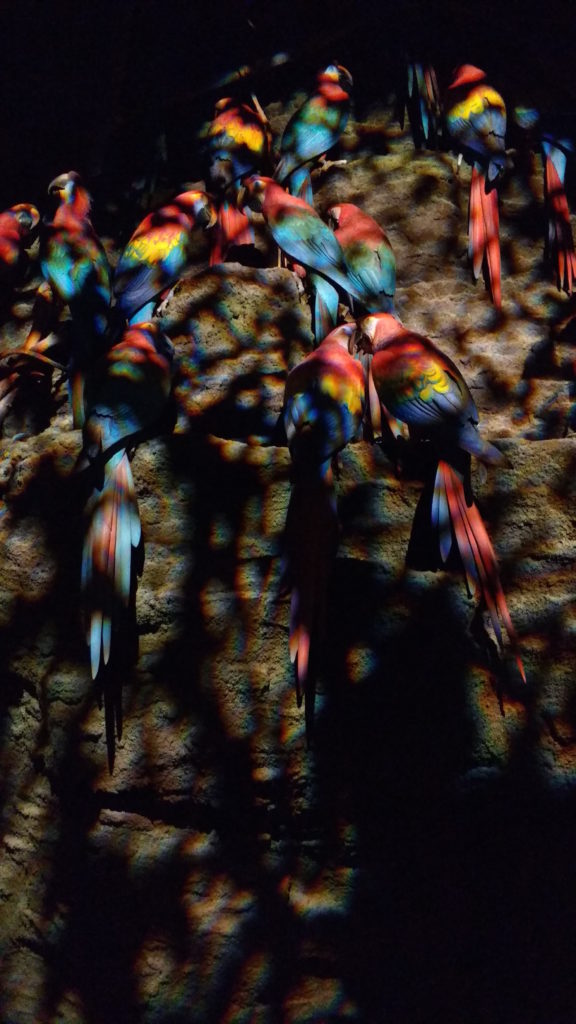

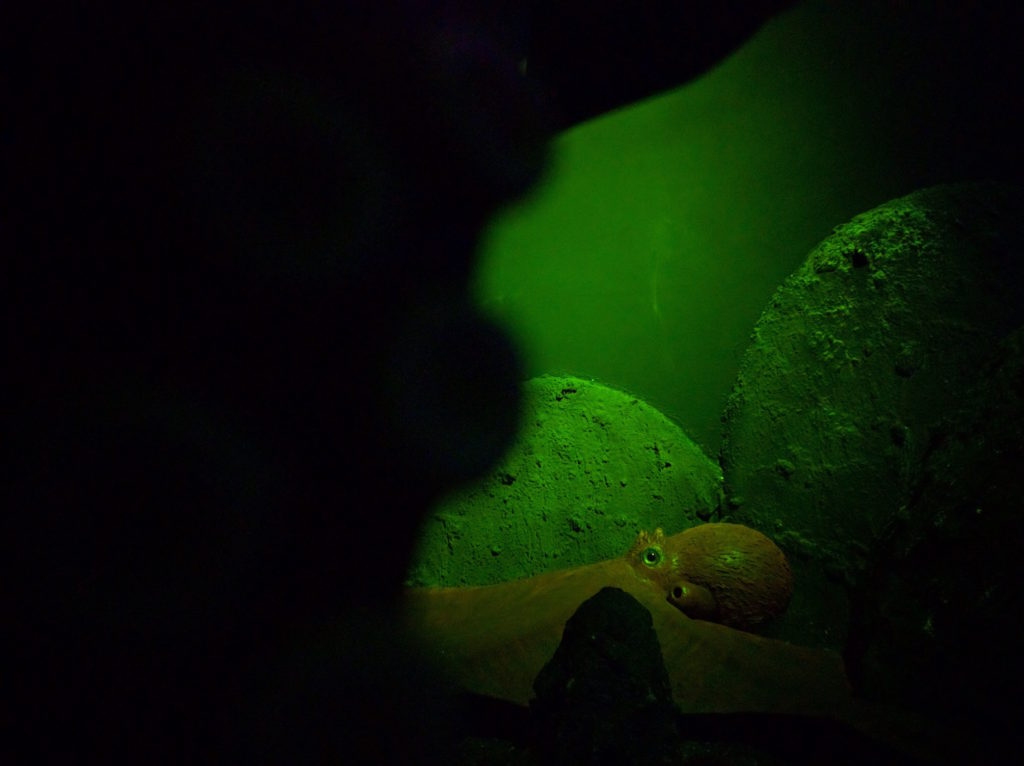

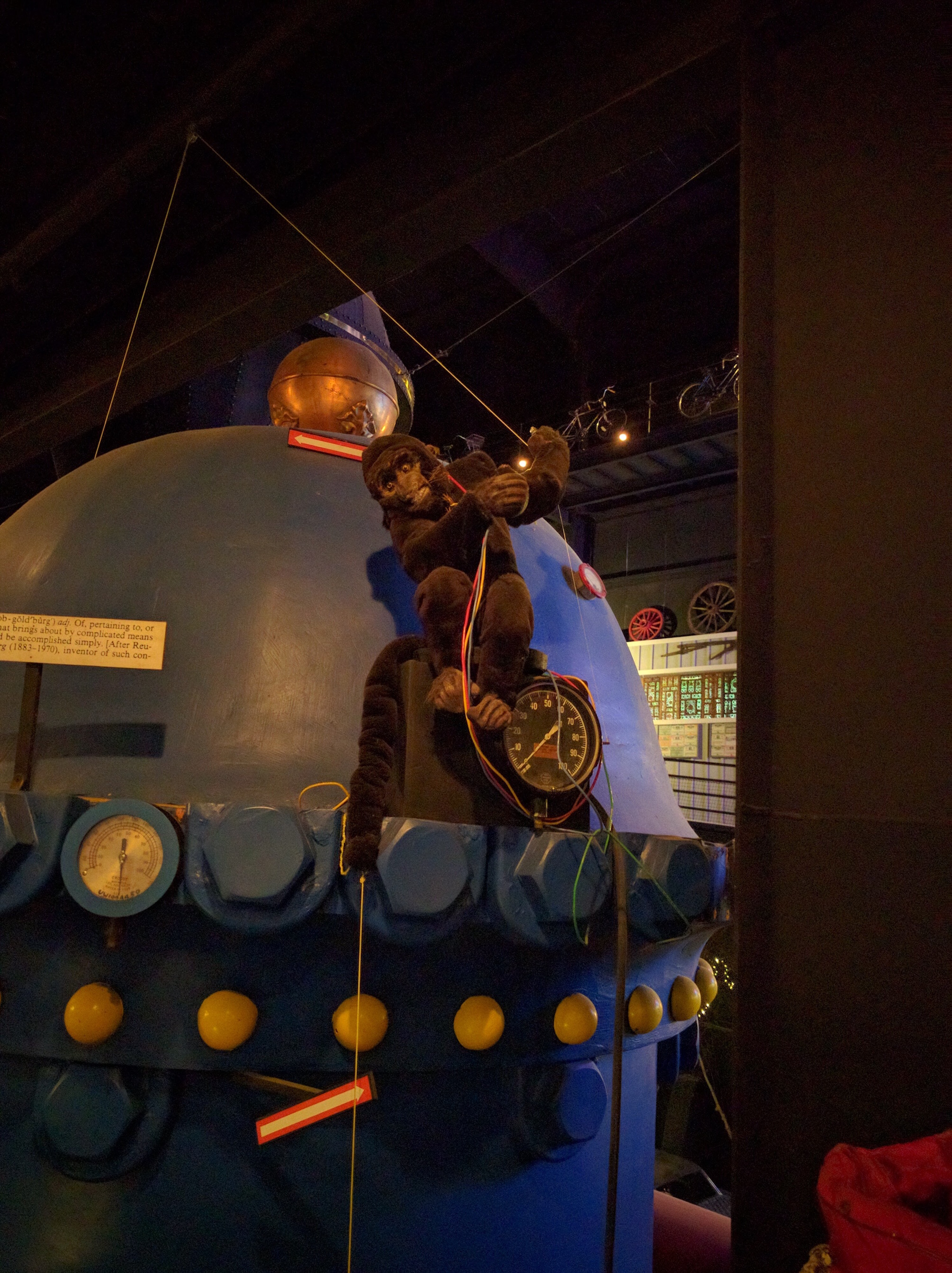

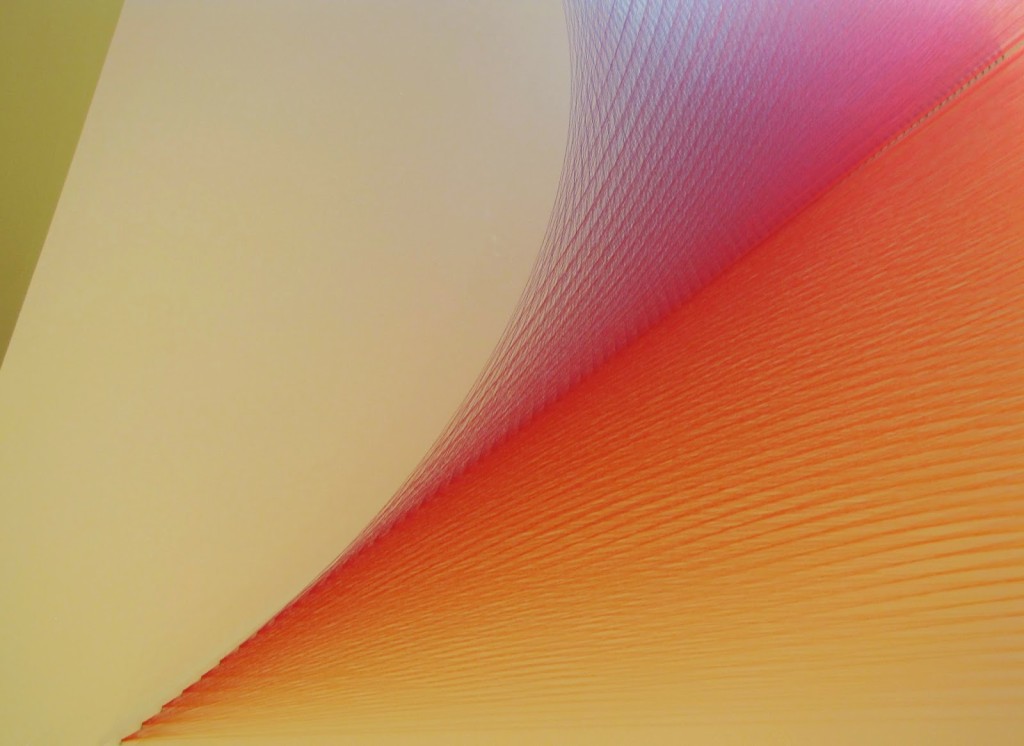

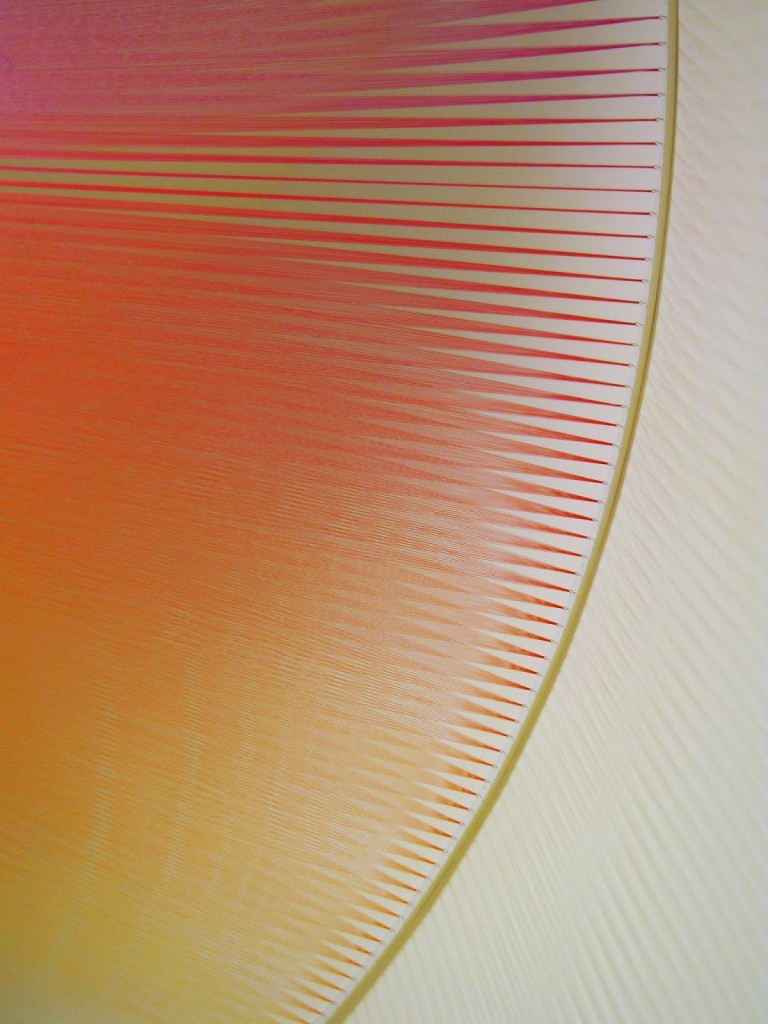

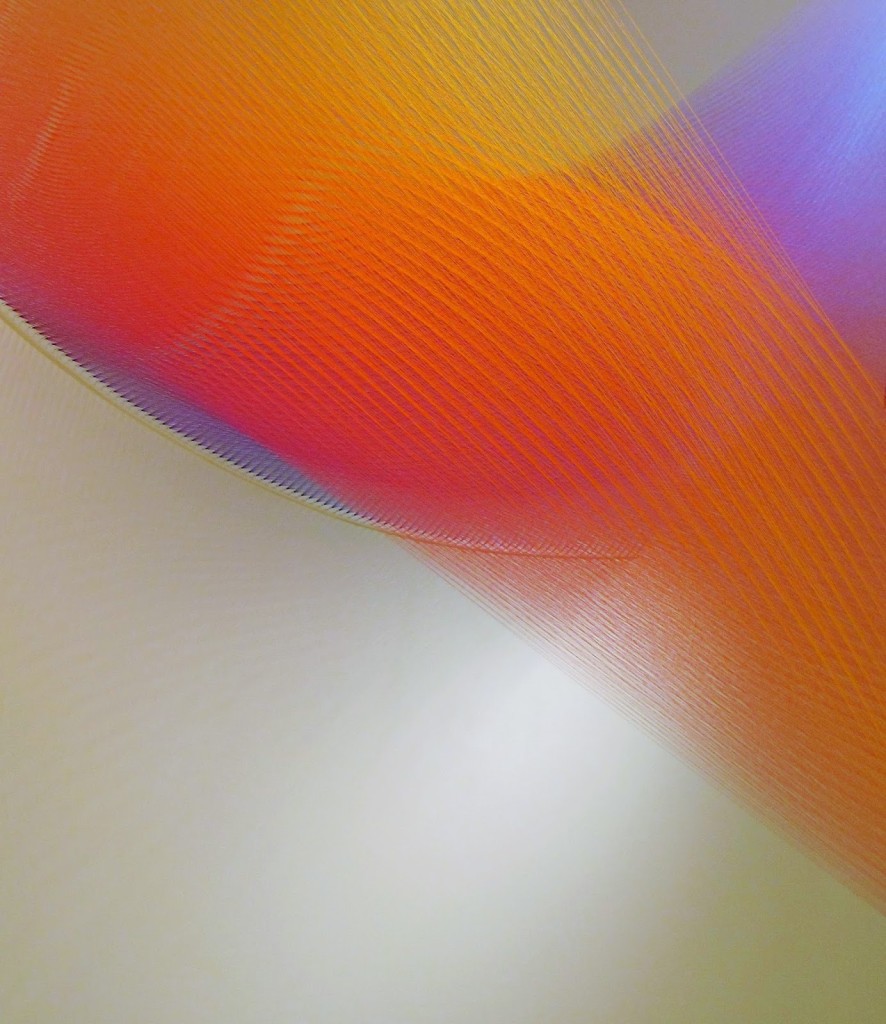

The Gran Museo divides its gallery spaces into two physically separated sections. During our visit, the first held an exhibition that was both innovative and straight-up weird. We never did figure out exactly what the thesis of the show was supposed to be (something related to evolution or extinction or how different cultures interpret the natural world?), but it included information on meteors as well as living, imagined, and extinct animals using geological fragments, fossils, European Renaissance prints, replicas of Maya artifacts, and a life-size installation representing the extinction and evolution of dinosaurs. Despite the jumble of ideas apparent throughout this section, most of the actual objects were interesting, while the unusual juxtapositions between seemingly unrelated items kept us engaged as well as confused.

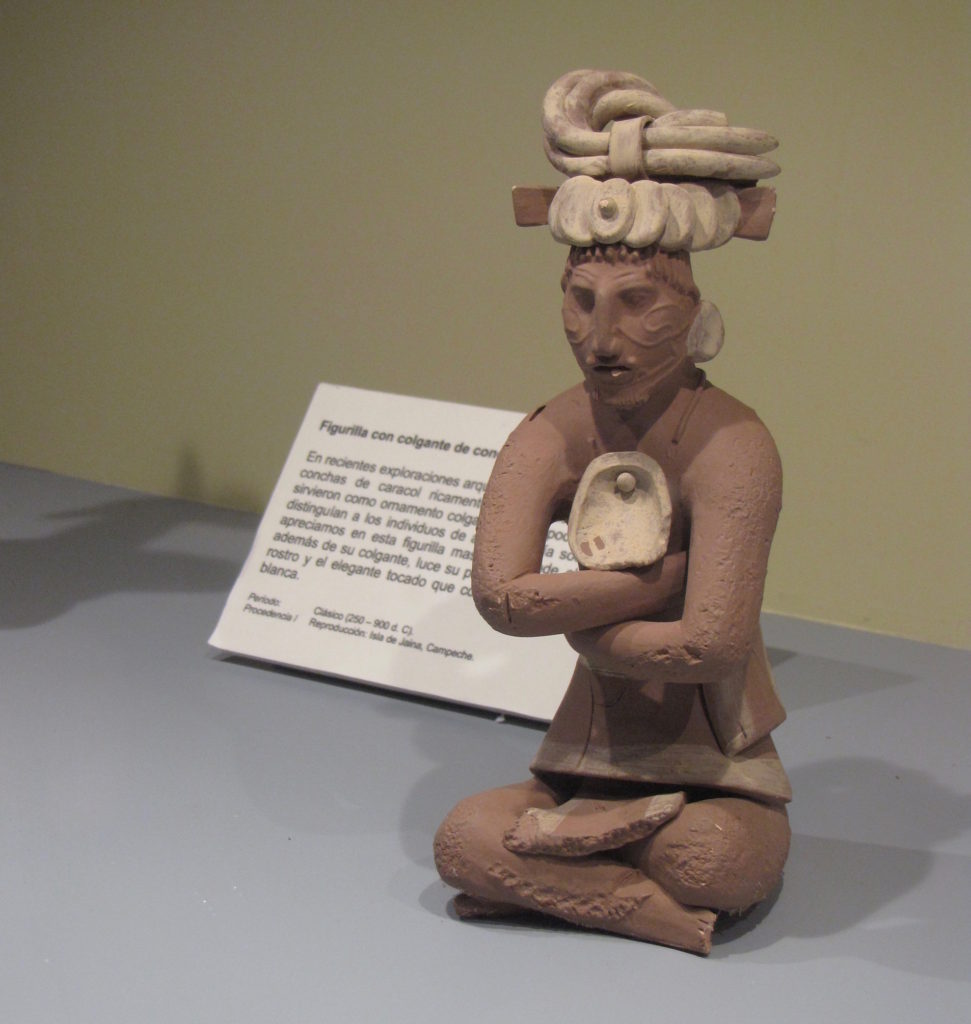

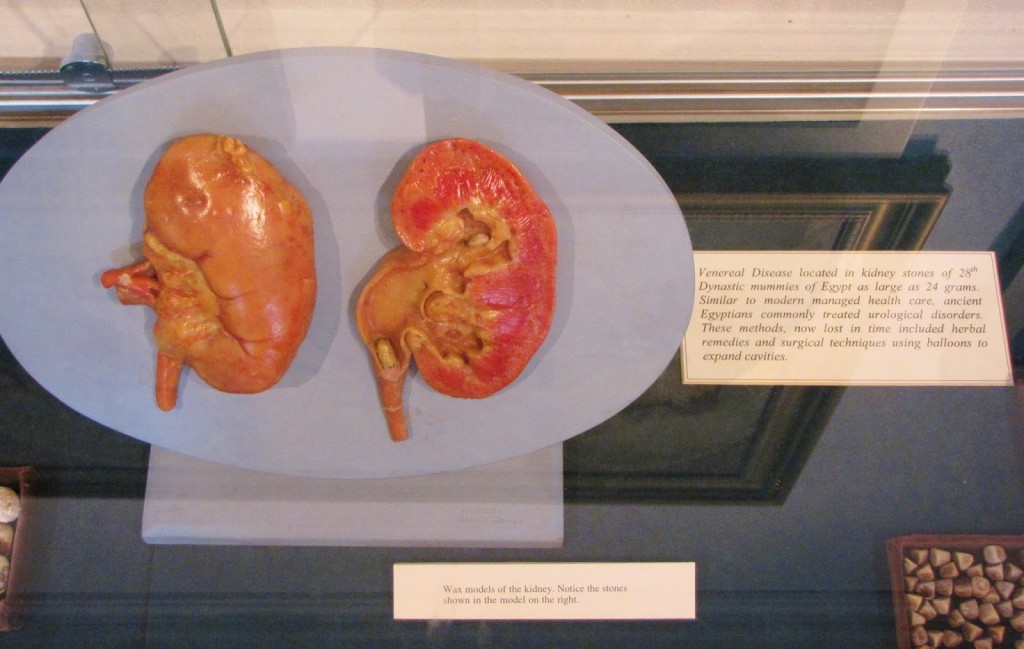

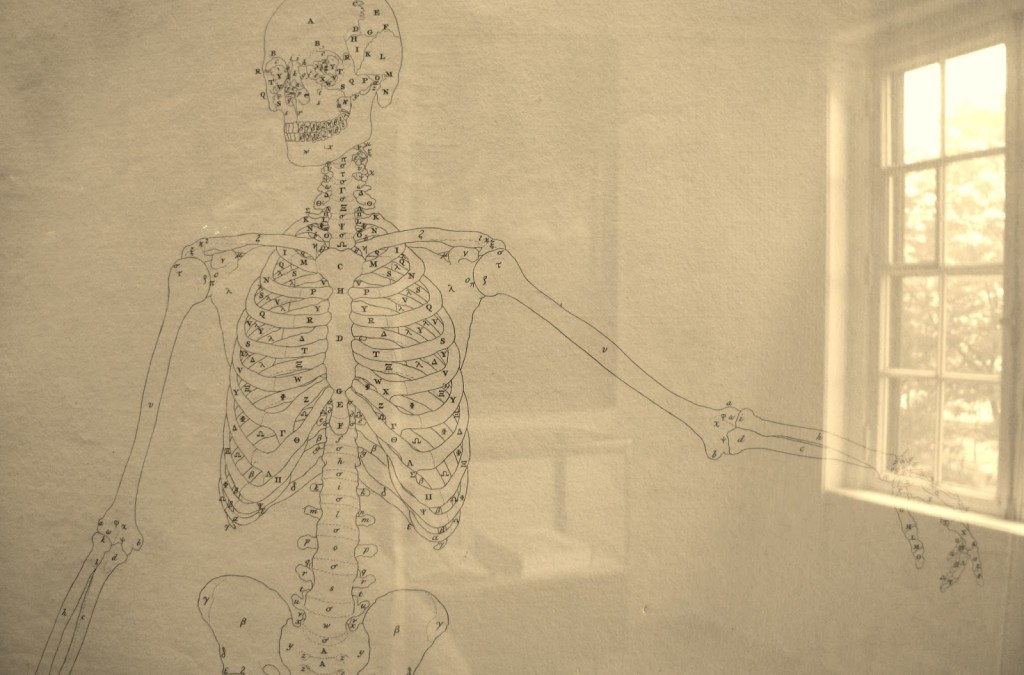

Even so, I will admit to being relieved when we entered the second section, dedicated to Maya history and the museum’s permanent collection of artifacts. These galleries alone are well worth a visit to the Gran Museo, as they include a plethora of fascinating objects, many of which diverge significantly from what you can find in textbooks or even specialist publications on Maya cultures. Also refreshing were the explanatory texts, many of which appear in Spanish, Mayan, and English and reflect a perspective that somehow feels both personal and scholarly.

Highly subjective personal rating: 8.5/10 [strongly recommended]

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 21, 2015.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 26, 2015.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 26, 2015.

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)