Photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz and Joshua Albers, August 9, 2014.

Tag: Joshua Albers

Holy Cross Abbey, County Tipperary, Republic of Ireland

From Cashel we took a slight detour north in order to visit the late Gothic church of Holy Cross Abbey, located near Thurles in County Tipperary. Named for its relic of the True Cross, the abbey was restored in the late 20th century and is once again in use as place of worship and pilgrimage after spending centuries in ruin.

Holy Cross was initially founded in 1168 or 1169 by Donal Mor O’Brien for the Benedictines. However, O’Brien transferred ownership to the Cistercians in 1180, and the abbey remained in their care until its eventual suppression. The current structure was built in the 15th century and contains a number of fine Gothic details, including sculpted pillars and remnants of a frescoed hunting scene. Although much of the sculptural decoration displays an unusual degree of refinement, the abbey’s most charming and surprising features are the numerous symbols subtly carved into the interior’s stone walls like labor-intensive doodles.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 29, 2013, unless otherwise indicated.

Muckross Friary and Killarney National Park, County Kerry, Republic of Ireland

A gem hidden within the grounds of Killarney National Park, Muckross Friary is located about a mile (on foot) from the parking lot of the sprawling mansion known as Muckross House. The monastery was once home to the strict order of the Observantine Franciscans, but had a relatively short life as a working friary. In 1541, only about a hundred years after its founding, Henry VIII ordered Muckross’s suppression. It was re-established in 1612, but Cromwellian forces finally drove out the inhabitants and burned the structure in 1652.

Today, Muckross’s most notable feature is the old yew tree that rises dramatically from the center of its cloister. Its bell tower, which was a later edition to the building, is also unique to Irish Franciscan buildings in that it spans the full width of the church.

The trails in Muckross Estate are easily managed and bountifully lined with twisting trees and fields of flowers. However, if you prefer not to walk, jaunting cars (aka, horse-drawn carriages) are available for hire at the parking area by Friar’s Glen and Torc Waterfall. Their eager drivers compete to take tourists past the sites along Muckross lake, and are willing to bargain with would-be passengers. The ride should cost around 5 Euro.

Ennis friary and cemetery, County Clare, Republic of Ireland

The earliest remains of the Franciscan friary at Ennis (Inis) date to the late 13th century, although much of the building actually comes from the second half of the 15th century. Founded around 1285 under the royal patronage of the O’Briens, Lords of Thomond, the friary soon became a burial site for kings and earls, and the town of Ennis grew up around it. By 1617, only one friar remained.

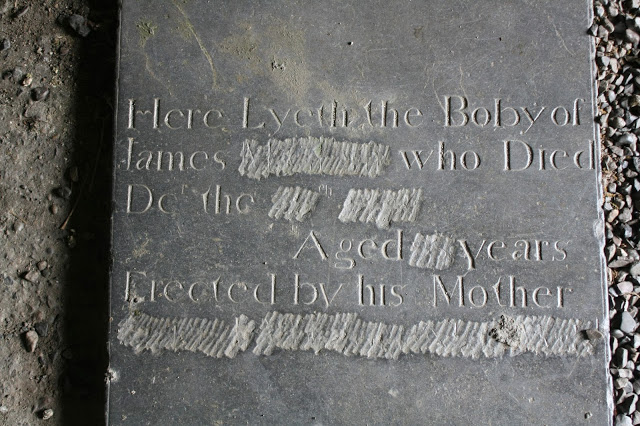

The site was undergoing a major reconstruction project while we were there, and relatively little of the decoration was in situ. Even so, Ennis possesses a number of fine examples of Irish Renaissance relief sculpture in its interior and decorated gravestones in its cemetery.

Ross Errilly Friary, County Galway, Republic of Ireland

Ross Errilly Friary is probably the best preserved Franciscan monastery in Ireland; it is also one of the largest. Yet the site is curiously absent from many guidebooks and harder to find than more tourist-ready destinations. As a result, we found it gloriously uncrowded.

Founded in 1351, the monastery was enlarged in 1498 and ultimately abandoned in 1753. Now left largely unguarded, the remains sit beside a slim stream amongst sprawling cattle pastures.

The central cloister demarcates the boundaries of the more private spaces of the monks’ former living quarters from the church and bell tower. The domestic sections include a bakery, kitchen (complete with a water tank for live fish), dining hall, and, on the upper floors, dormitories. The presence of more recent graves throughout the building suggests that the entire structure is still on consecrated ground.

Photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 26, 2013, unless otherwise stated.

Sligo Friary, Sligo, County Sligo, Republic of Ireland

Back in the Republic of Ireland, we decided to call it a day and spend the night in the port town of Sligo (Sligeach), which Wikipedia tells me is the most populous area of Sligo County. It is also the setting for Sebastian Barry’s bleak but beautiful novel, The Secret Scripture, which relates the history of 20th century Ireland through the life of a nearly 100-year-old mental patient.

Despite Barry’s less-than-complimentary depiction of Sligo as a town defined by its harsh weather, closed minds, and divided politics, we found the people friendly and the city center, perched along the River Garavogue, lovely. It was also surprisingly popular, and we had to try several B&Bs before we could find one with a free room.

Most places were closed by the time we settled-in on Saturday evening, so we decided to wait for the friary to open before leaving in the morning. As a result, we were the first people there and had the site almost entirely to ourselves for the duration of our visit.

Although popularly known as Sligo Abbey, the monastic ruins near the town’s center are technically the remnants of a Dominican friary. The terminological slippage is quite common—most “abbeys” in Ireland are in fact friaries—and quite understandable, as the two types of structures are nearly interchangeable in both function and appearance. The most basic difference is simply that monks (and abbots) lived in abbeys, whereas friars lived in friaries. Because a monk’s lifestyle was generally private—focused on personal prayer and meditation—abbeys tended to be closed to the broader public. Friars, on the other hand, went on preaching pilgrimages and encouraged their communities to worship in their churches. Architecturally speaking, the differences are even more subtle. Friaries usually have tall, narrow bell towers, while an abbey’s tower is relatively short and broad.

Sligo’s friary was founded in c. 1253 by Maurice Fitzgerald when the town was still a Norman settlement. Some of this early building survives, although much of the friary was rebuilt in the 15th century. Its most unusual aspects include a 15th century rood screen, two elaborate tomb monuments, and the only remaining sculpted stone altar in Ireland.

Although the altar is probably the most significant feature of the site, we were even more taken with the local Gastropods, particularly the large and rather weathered specimen we still affectionately refer to as “the Sligo Snail.” Perhaps the most expressive invertebrate I’ve met, we watched him/her devour flowers for at least a quarter of an hour. If you’ve never seen a snail eat, I recommend checking-out Josh’s time-lapse of the process. It’s kind of adorable.

Unless otherwise stated, all photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 26, 2013.

Reyfad Rock Art, Boho, County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland

With no signage for either the site or the landmarks leading up to it, the Neolitihic and Iron Age stones in Boho are easy to miss and difficult to find. Predating the megalithic art at Newgrange and Knowth by as much as 2000 years, the site is also a great stop for those who prefer their artifacts in situ and enjoy some challenge in their travels. For everyone else—particularly those short on time or who would prefer a bigger pay-off for less effort—the National Museum of Archaeology in Dublin has a fine collection of prehistoric art from the island.

We never would have found our destination without the directions posted by Jim Dempsey at Megalithic Ireland. Even with Dempsey’s helpful hints, we came very close to giving up the chase after realizing that the fields containing the megaliths were covered in stony outcroppings, several of which seemed to be possible candidates for the particular rocks we were searching for. However, having spent hours trying to locate the site, including some tense minutes driving up and then backing down the long, rough, single-lane road that serves as the only access to the area, we finally decided to park, find a way through a low wire fence, and wander towards the shiniest, flattest, most promising cluster of stones.

To our surprise, our series of hunches and hopes had in fact led us to our destination.

Walking around pasture land without permission is an expected activity in Ireland, but it still comes with its potential dangers, particularly from the livestock who (fairly) view tourists as trespassers on their territory.

After finishing up and remembering our last encounter with cattle, I decided to wait on the other side of the fence while Josh continued taking pictures. From this higher vantage point, I noticed a lone black cow moving stealthily towards Josh, watching him and stepping forward while his back was turned, then grazing disinterestedly whenever he turned around.

Freakin’ Irish ninja cows.

I encouraged Josh to finish up, and we were once again on our way towards the border of the two Irelands.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 25, 2013.

Caldragh Cemetery, Boa Island, County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland

We left Dunluce Castle and the northern coast to begin our descent south and west. Our new route took us off of the “M” motorways—those broad, smoothly paved passages which extend from Dublin and Belfast across the eastern regions—and onto the network of narrow, winding roads that connect the rest of the island. Suddenly, our destinations seemed much further away.

Having swapped the great, straight swathes of pavement for slender, twisting lanes, we were also headed towards quieter and more secluded landmarks near the border of the two Irelands.

Our first stop was Caldragh Cemetery on Boa Island. A spit of earth along the northern edge of Lough Erne (aka, Lake Erne), Boa Island is accessible by car thanks to bridges connecting its central road to the mainland. The island is lovely in and of itself, but the primary draw for tourists is Caldragh Cemetery and its two mysterious inhabitants: the Janus Figure and the Lusty Man.

To reach the cemetery, we turned off the main road onto what appeared to be a long, unpaved driveway. The lane terminated after about a mile beside rusting farming equipment and a small footpath. Even on a Saturday afternoon, ours was the only car around.

The site immediately impresses with the sheer lushness of its environment. Gnarled, ancient trees draped in vines encircle the clearing while bright blue, yellow, and white flowers punctuate a fluorescent landscape of broadleaf plants and long, soft grasses. The overall effect is one of a kind of quiet, bountiful life that only cemeteries seem to have.

Consistent with the natural understatedness of the site, the statues are almost indistinguishable from the tombstones around them. From a distance even the Janus Figure–the larger and better preserved of the sculptures–appears to be an only slightly grander grave marker. As its name implies, the Janus Figure (also known as the Boa Island Figure) consists of two back-to-back male faces. Its small, headless torso lies in the grass beside it.

The Lusty Man now sits a few feet away, but was originally discovered in a cemetery on the nearby Lusty Mor Island. It was moved to its current location in 1939. The exact ages, purposes, and identities of the figures are unknown, although both are probably pre-Christian.

Photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 25, 2013.

Dunluce Castle, Bushmills, County Antrim, Northern Ireland

A few miles west of Giant’s Causeway, the skeletal remains of Dunluce Castle stand perched on a cliff along the North Channel. A deep ravine divides the site into two sections which are linked by a narrow, pedestrian bridge.

The side closest to the road held the stables and guest quarters (and now houses the visitor center), while the second area—with the buildings most precariously balanced over the sea—served as the primary residence.

Access to the buildings is only possible during certain hours and requires a small fee, but a steep, unguarded staircase to the side of the restricted area leads to the lowest point between the two sections. From here, visitors will find impressive views of the ruins and surrounding landscape, and can take a closer look at the small cave beneath the furthest outcropping.

Richard de Burgh or one of his followers probably built the original castle in the 13thcentury on the site of an earlier fort. However, it’s best known as the home of the McDonnells, chiefs of Antrim, who took control of the building after the Battle of Orla in 1565. Randall McDonnell, the second McDonnell lord at Dunluce, was responsible for erecting the manor house within the fortress’s walls. In 1639, part of the castle fell into the sea, taking the kitchen and cooks with it. The buildings were ultimately abandoned in 1690.

Photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 25, 2013, unless otherwise stated.

Knowth, Brú na Bóinne, County Meath, Republic of Ireland

At the end of May, Josh and I took an eight day trip to Ireland. We emerged, windswept and damp, with over 5,000 photographs, which I have since whittled down to more reasonable, post-sized selections.

The art and history of Ireland are outside my particular expertise, so the information included in these posts has been culled from guidebooks (DK and Lonely Planet), related websites, our many lovely guides, and a variety of materials provided at the sites themselves.

Our first day outside of Dublin began at Brú na Bóinne, one of the island’s three UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The valley of Brú na Bóinne contains three Neolithic centers—Knowth, Newgrange, and Dowth—each of which possesses a great mound (large passage tomb) and smaller satellite graves. Only Knowth and Newgrange are open to visitors, and these are only accessible through tours provided by the visitor center. Such stringent oversight is unusual in Ireland, but it allows for better preservation of these important, fragile monuments.

Knowth is the first stop for those who choose to visit both open sites. Of the three centers, Knowth is the oldest, was utilized for the longest period of time (up to about 1400), and is arguably the most complex.

Knowth’s great mound possesses two entrances (referred to as the “male”/western and “female”/eastern chambers due to their relative shapes), but visitors can only go into a contemporary passage and small exhibition space near the less impressive western passage. Chunks of white quartz and dark, rounded granite are scattered on the ground around both entrances of Knowth, while the same kinds of stones have been reconstructed into supporting walls at Newgrange. This discrepancy is probably more reflective of changes in archaeological practices and philosophy towards reconstruction than a difference in original use and placement at the two mounds.

More importantly, Knowth boasts the largest collection of Megalithic art in Europe, most of which is still in-situ. A good sampling can be found on the slabs, or kerbstones, around the base of the central mound, although much of what exists is located in the primary but inaccessible “female” chamber.

Knowth also differs from Newgrange in that the site includes a number of smaller satellite passage tombs clustered closely around the central mound.

Although all passage graves contain cremated human remains, it is likely that the great tombs also had additional, ritualistic functions, as suggested by the fact that their passages were tall enough for people to walk through, and each was lit at either a solstice or equinox.

Knowth and Newgrange were also once sites of woodhenges (reconstructed at Knowth), which post-date the mounds by several centuries. Like the large passages, these henges were arranged to correspond to significant dates in the year’s cycle.

At both sites, archaeological reconstruction was aided by kerbstones which ring the bottom of most passage tombs; similar large stones line the interior passageways of the primary mounds. Abstract imagery—particularly spirals, circles, and undulating lines—has been engraved into the surfaces of over a hundred of the boulders. It is unclear what, if anything, these “symbols” represent, although they may depict aspects of the landscape, particularly the sun, rivers, hills, and even the mounds themselves.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz, May 24, 2013, unless otherwise noted.