Suicide is like a lump in the throat of those left behind. It indicates the presence of issues that need to be discussed, but also creates a barrier to that discussion. I therefore beg your patience with the awkwardness of this post.

Last week began under the pall of suicide when a performance artist in my husband’s graduate program killed hirself by jumping out of a 5th floor studio window. Out of deference to hir own investment in gender ambiguity and in an attempt to maintain some of hir family’s privacy, I will refer to this student as “M” with the pronouns s/he, hir, and hirself.

I only met M once, but I liked hir and hir work immediately. As a performance artist who integrated hir life and production, s/he came across as outgoing, open, and bold. Performance art is perhaps the most difficult area to make a living in, yet to my eye M had real potential to make a name for hirself in the field.

So even as someone who barely knew hir, learning of M’s apparent suicide was a shock, and the days following have been underscored by sadness and unease at the realization of hir sudden and final absence. As with any unexpected death, one of the first questions after how, where, and when is why. But when we ask that question—especially when no answer is definitively left behind—the most alarming realization is the discovery of how easy it is to come up with reasons why someone in our current environment would choose to die. This is particularly true for an artist who was not only about to graduate into a terrible economy, but who was also openly part of the LGBT population in a society that is almost schizophrenic in its treatment of queer identity.

But the thought that most disturbs me, and that is the most difficult to even mention, is that hir suicide may also have been hir final work. It seems dangerous—even potentially disrespectful—to mention this possibility, and yet it is not as far-fetched as it might first sound. Again, M already self-consciously made work that was synonymous with hir life experience. It also would not be the first time an artist either orchestrated his own death as a final magnum opus or died as a result of a particularly dangerous project. Ray Johnson (whose life and bizarre death are the subject of the documentary, How to Draw a Bunny) and Bas Jan Ader (who disappeared at sea in 1975 while trying to cross the ocean alone in a tiny vessel for his work In Search of the Miraculous) are perhaps the most obvious examples. Finally, and most horrifyingly, at the time that s/he jumped to hir death, M was preparing for a group thesis exhibition which s/he had helped to title Splatter Platter.

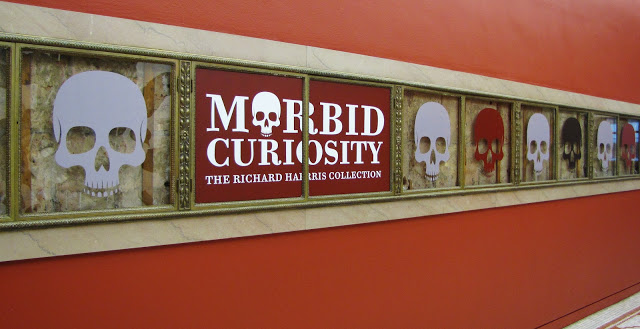

Coincidentally, I ended my week at Morbid Curiosity: The Richard Harris Collection, an exhibition at the Chicago Cultural Center dedicated to depictions of death. As exemplified by this show, death as the result of political atrocities or as an abstract subject made visible through memento mori or codified in religious paraphernalia is a relatively common, even comfortable, subject in art and art history. What is much more difficult to breach is the idea of death as art. Even for a field in which self-mutilation and deprivation have become recognized practices for performance artists, this final taboo is one which we dare not broadly acknowledge.

Undoubtedly our collective squeamishness around this subject exists in no small part because public consideration of suicide as a form of practice can too easily fall into encouraging suicide, which, of course, no one wants to do. Yet this most extreme fusion of life and practice appears to be a real phenomenon whether we acknowledge it or not, and one that raises a number of important issues and questions that go to the heart of what it means to direct and shape one’s own life.

I think we are on the brink of having to deal with the subject of suicide in art as something broader than an individual or peculiar occurrence. How we deal with this morally, ethically, legally, emotionally, and practically difficult topic, though, is a complex challenge only the most daring individuals and (eventually) institutions will be willing to take on.

Whatever the circumstances of M’s death, hir abrupt loss represents an all-too-common tragedy, particularly for the friends and family s/he left behind. Right now, perhaps that’s all there really is to say.

All photos by Renée DeVoe Mertz.